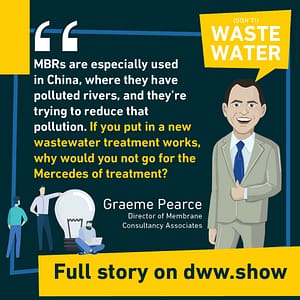

Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs) are arguably the fastest-growing segment of the Water Industry. In China alone, the yearly investment for the next five-year plan shall reach $7 Bn (together with their cousin MABR and MBBR systems).

This summary article goes into the key features of MBR systems while citing relevant quotes from the conversation that I had on the podcast with Dr. Graeme Pearce, Principal at Membrane Consultancy Associates, and an expert in membrane treatment for 40 years.

This is one of the sections of my deep dive on water and wastewater treatment!

Table of contents

- What is a Membrane Bioreactor (MBR)?

- What are the pros and cons of MBRs?

- A bit of History: the rise of Membrane Treatments

- Where do Membrane Bioreactors come from?

- China hosts 65% of the World’s installed Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) base

- Anatomy of a membrane bioreactor (MBR)

- Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs) as a plant upgrade?

- When it comes to Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs), size matters!

- Conclusion on Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs)

What is a Membrane Bioreactor (MBR)?

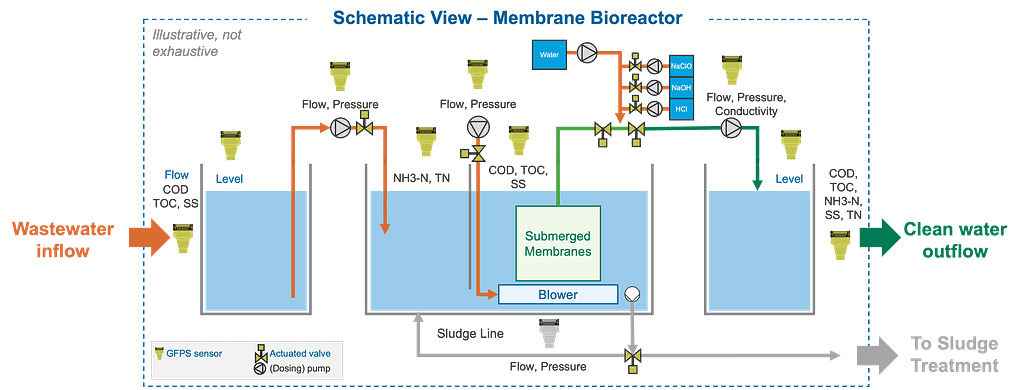

First things first, let’s define it. A Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) is the combination of a biological reaction stage and a membrane barrier.

The membranes used in an MBR can be ceramic or polymeric – with currently higher growth in ceramic membrane solutions. The membrane pore size usually applied is in the ultrafiltration range, and the design whether flat sheet or hollow fiber (more to that in a minute).

How does an MBR work in a Sewage Treatment Plant (STP)?

A membrane bioreactor enables the replacement of the traditional activated sludge processes in combination with clarifiers in one single step. Indeed, the biological treatment remains pretty similar to an activated sludge process, but the submerged ultrafiltration modules also clarify the feed in place. Welcome side-effect: wastewater even gets treated to a higher level of purity, as the membrane filtration goes beyond traditional clarifiers to also replace a post-treatment such as sand filters.

To cut a long story short: MBR is an all-in-one wastewater system, that makes it an ideal fit, especially in smaller size plants where it doesn’t need to seek the activated sludge’s scale effect.

Where is MBR used?

MBRs are primarily used in wastewater treatment. That being said, as they evolve on the border between wastewater and water reuse, they can also be seen as a primary treatment for drinking water. Hence, more and more, as water reuse gets enforced, MBRs tend to become an all-rounder process, targeted at reducing organic compounds.

What are the pros and cons of MBRs?

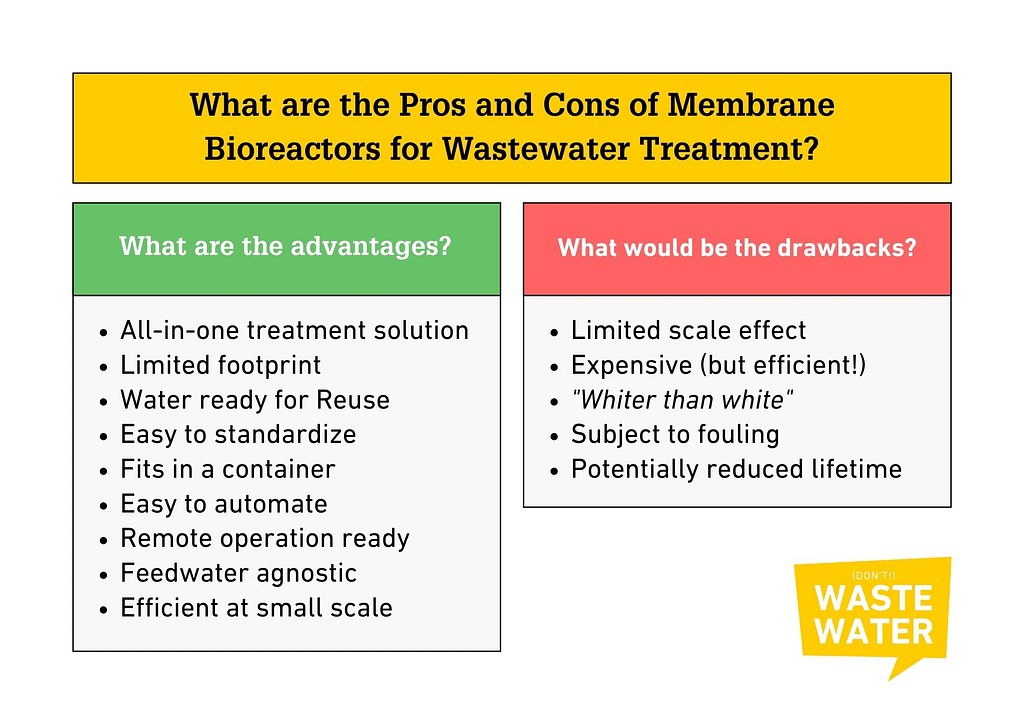

I’ll expand on that in a minute, but here’s already a summary of the perks and limits of the system we review today:

What are the advantages of MBRs?

- Membrane Bioreactors are an all-in-one treatment solution, that offers high treatment performances in a limited footprint

- MBRs produce water that’s ready for reuse straight at the outlet in most applications

- These processes are efficient at every scale, which makes them an ideal fit for small-sized facilities

- MBRs can be containerized, and are easy to automate. They also can be operating from remote

- The performances of a membrane bioreactor are stable over time and heavily agnostic of the raw water quality

What are the drawbacks of MBRs?

- As MBRs are performant on every scale, they also offer limited scale effects. So basically, a large MBR plant will simply cost a multiple of a small one, which makes them less pertinent on a very large scale

- Membrane biological reactors produce a water quality that’s often above the regulation requirements, so they may wash whiter than white

- The overall cost of a Membrane Bioreactor is often higher than a conventional system (but it also delivers higher treatment performances)

- Even if the process is raw water agnostic, it can be subject to faster and more problematic fouling in some conditions, which leads to higher maintenance costs and sometimes shorter lifetimes.

A bit of History: the rise of Membrane Treatments

Although membranes had been around since 1748, and the discovery of Osmosis by Jean-Antoine Nollet, their large-scale adoption in the water industry has taken quite a while. The reason is shared by Graeme Pearce in his podcast interview:

Getting the pore size under control would take membrane manufacturers a mere two centuries. The first breakthrough was achieved in Germany in the 1920’s, when Nobel-Prize winner Richard Zsigmondy teamed up with Sartorius AG to produce commercial-scale Ultrafiltration membrane systems.

Crossflow filtration and polysulfone membranes would then appear in the 1960s. And specialized companies in the US were addressing niche applications. Nothing that would significantly move the needle!

But change was around the corner: petrochemical companies started looking into separation research, quickly identifying membranes as a promising horse to bet on. This happened in the 1980’s, and this is also when Graeme Pearce joined BP.

From BP Research to Standalone Membrane Company

At the times, BP became excited about separation research, to the point that by 1988, 80 people were working full time on R&D in this field.

This of course had a cost so BP started seeking payback, thus founding BP Ventures Company. That wouldn’t last: BP quickly sought to sell it. And Graeme, at the time, Process Engineering Manager of the company, teamed up with the other executives to do a management buy-out. This led to the foundation of Kalsep!

During the BP times, the membrane systems had been investigated as an alternative to distillation. But the newly inducted start-up aimed at a pivot, focusing instead on the water market, its higher flux, and organic pollution to combat.

A membrane adoption curve suddenly sped up

In doing so, they escaped a conservative market, not really ready to adopt membranes to focus instead on… another conservative market, not much more ready to do so.

But change was around the corner. In the UK and in the US, outbreaks of cryptosporidium emerged as a new threat to water treatment. This parasite, about four microns in diameter, was indeed small enough to get through conventional treatment. Yet membranes were a complete barrier!

As Graeme recalls, legislation created a strong driver for membranes, by enforcing complete removal of that microorganism.

In continental Europe, the driver was a bit different, the focus being less on this parasite. Instead, countries like Netherlands or France wanted to reduce their chlorine dependency. Hence they saw membranes as a universal barrier to viruses and microorganisms. Simply put: a way to increase water quality without chlorine’s drawbacks.

Fast-growing membrane companies

With regulations enforcing the use of membranes in a significant portion of the world, Kalsep experienced significant growth.

A full sector of the drinking water industry was almost built from scratch in under a decade. But as you might expect from an article called “Membrane Bioreactor” from its title, it would not stay parked there!

Membranes had a lot to offer in other parts of the water sector, starting with wastewater treatment.

But as with all rapid growths, some childhood diseases also appeared. Companies were too aggressive with their designs, or products simply did not withstand the test of time. This led Graeme to enter the consultancy world, to have the opportunity to be more agnostic and objective.

This makes him even more of the coolest guide there is, to discuss objectively Membrane biological systems.

Where do Membrane Bioreactors come from?

But to better understand where it comes from, and what it can achieve, let’s go back to the roots of MBRs.

The initial advocate for this Idea – weird at the times – was Zenon. Long before merging into GE Water then SUEZ (then maybe Veolia ?), Zenon had a vision.

But by then, nobody really paid attention. And when they got more than crickets, the reaction was along the lines of “too expensive” or “never going to work”. (quite a lesson of innovation, right?)

The two drivers that helped Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs) to become a thing

So while Zenon was professing in the desert, two drivers slightly helped.

The first was a regulation reinforcement on wastewater discharge to rivers and allowed pollution loads.

Indeed, the EU directive, first adopted in 1991 and then augmented in 1998 wasn’t expressively calling for treatment levels only achievable with membranes. So it was sure less of a driver than the cryptosporidium one on the clean side. But still, it pushed companies to improve their wastewater treatment, which gave Zenon a lever for conviction. (And utilities a nudge for operating a change.)

The next driver came quite later but is a bit stronger. It’s the driver for reuse.

This time, membranes are almost a go-to to achieve the desired treatment levels. But in many countries, those regulations are still in their baby pants and regulators tigers without teeth.

So Membranes as biological systems to increase wastewater treatment plants’ organic removal yield had to be enforced differently, without the strong supporting hand of regulations. Surface water’s protection came at that cost, at least.

Is a Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) simply better?

Why would a technology still get adopted, if it’s at first more expensive, and not made mandatory by legislation?

Well, let’s check the existing standard when Membrane Bioreactors first appeared. Your Wastewater Treatment Plant relies on a biological treatment within conventional activated sludge tanks. Microorganisms break down the nutrients and create sludge. This sludge then settles in clarifiers, and you might sometimes drive all of this on sand filters to remove some of the remaining solids.

That’s the status quo, and it’s around since the beginning of the XXth century.

So, membrane biological treatment systems turn wastewater treatment into a small, compact, and efficient process. Which is awesome, but also makes hardware such as concrete tanks redundant. (as you can run higher flux on less footprint!)

That made adoption difficult in Europe because the radical disruption did not allow for the smooth reuse of legacy installations. But in other places, that would just fit perfectly!

China hosts 65% of the World’s installed Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) base

Take a country like China. They had limited to no existing infrastructure, yet they needed to treat wastewater to protect the environment and above all their industry.

So does that mean that MBRs are superior in any aspects to conventional activated sludge? Well, it still depends on your intended treatment level.

If you’re like China and aiming at “Class 1A” waters, then probably yes. But if the quality of the discharged water can be a bit lower, then conventional treatments are still less expensive.

The footprint element is equally important: in a country as crowded as China, with ever-growing cities, you cannot afford large Victorian Water Works as you would see in London.

Membrane bioreactors (MBRs) as an industrial wastewater treatment

Now, if we stay on that footprint element, there is another place besides Chinese Cities where it is a killer argument: in industries.

Footprint saving is a strong driver for the booming adoption of MBR in industrial wastewater treatment, yet not the only one. Another important aspect is the return on investment (ROI).

Conventional treatments might be a bit cheaper in operation than an MBR, but they imply heavy civil works investment. Altogether, it builds for a close call when it comes to total costs of ownership in the municipal world, where you’re calculating with 20-30 years of investment.

But in the industrial world, amortizing times are much shorter, hence the Membrane Bioreactor solution is even more appealing.

Last but not least, Membrane Bioreactors are very forgiving when it comes to changes in the water quality. (Except for fouling, more to that in a jiffy)

That degree of tolerance actually comes from the membrane. But talking of membranes, what do they look like?

Anatomy of a membrane bioreactor (MBR)

Depending on the manufacturer (as for the MABRs), membranes used in MBRs might be flat sheets or hollow fiber. And their primary material historically was PVDF, but could as well become ceramics.

Polymeric vs Ceramic Membranes

But recent developments have placed ceramic membranes as an interesting alternative. Traction is still in the early stages, but ceramics allow for a very aggressive sort of mechanical and chemical cleaning. They also allow higher flux rate, and lower energy for a higher flow, as they operate at lower pressures.

Historically in the 90s, cost reasons have made polymeric membranes a go-to. And ceramic membranes were coming with a lot of costs in their manufacturing process.

So, if you can reduce those costs – and the labor input, what stays is the capital investment for equipment. And here again, higher produced amounts mean economies of scale. This comes on top of the performance advantage they offer, which pays them back in the long run.

On the other hand, ceramics are rigid, which slightly changes the way you operate your membrane bioreactor.

Now, you could replace this cleaning with an explosive backwash, which has the big advantage of being much more effective than the “aeration cleaning”.

Flat Sheet vs Hollow Fiber Membranes

Regarding shape and geometry, there is an overall leveling and smoothing of the argumentation. This is very true in the general membrane market, a bit less in Membrane Bioreactors.

in MBRs, the picture is still slightly different, with companies advocating whether for the one or for the other shape.

To distinguish between hollow fiber and flat sheet in membrane bioreactor technologies, there are some universal rules, as Graeme Pierce recalls:

Then, as often in wastewater treatment, it’s a case by case, one by one story.

Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs) as a plant upgrade?

We’ve seen that MBRs are an awesome go-to when there’s no infrastructure existing, and even more if space is limited and the quality of the effluent strictly regulated.

But be it in Europe, parts of the US, or in large chunks of Asia, like Japan or South Korea, many plants will be reaching their age limit in the next decade. Often, they now face higher incoming pollution, so they don’t only need to be refurbished, but also increased in terms of treatment capacity.

This is another sweet spot for “Membrane Biomass Killers”.

Now, if it has many perks, especially on footprint and process intensification, it is still not a silver bullet either. Indeed, it still remains a bit tricky, and expensive.

But by achieving this kind of upgrade, you turn a secondary treatment (conventional activated sludge) into a “tertiary plus” if not quaternary treatment – with spectacularly increased performances.

Reuse is a driver for Membrane Bioreactors MBRs

Now think of it. You’re like 50% of the US Wastewater treatment plants (representing about one-third of the sewage flow), and you solely rely on primary and secondary treatment.

If you were to upgrade your infrastructure and add a conventional tertiary treatment, such as a sand filter, you would sure improve the water outlet quality. But still not to reuse levels!

So now, if you consider instead upgrading to an MBR, you reach these reuse levels, be it for non-potable reuse, indirect potable reuse (such as aquifer recharge) or full-blown closed loops (through an additional polishing).

So again, as we’ve seen it previously, wastewater reuse is a driver for Membrane Biomass removal solutions.

When it comes to Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs), size matters!

We’ve seen the larger scale chunk of the market. But that’s barely a majority in flows: the distributed side, so the aggregation of smaller treatment units is the booming sector in the water industry for a reason.

And this distinction in size actually matters. Because on the largest scale, conventional treatments are hard to beat in cost-benefit ratio. But that changes with scale:

there are two rules to get, to understand this:

- Conventional Activated Sludge are living organisms with little appeal for high variations in flows and loads. This makes them hardly operable at small scale. Meanwhile, sturdy MBRs are much more flexible, thanks to the membrane element making it a good fit for low flows.

- MBRs are, even in their most advanced form, a series of standard building blocks. So scaling up Membrane Bioreactors equals to multiplying the number of modules, with thus limited economies of scale. On the other end of the spectrum, conventional treatments are always cheaper per m3 the larger they get.

A Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) is not a silver bullet (spoiler: there is no silver bullet in wastewater treatment!)

We’ve seen right now, that for very large plants, Membrane Bioreactors would probably be beaten by conventional treatments, because of the economies of scale.

We previously also addressed the case where, the regulation wouldn’t anyways enforce the quality that an MBR would deliver, thus making it overkill.

There’s a third case, where membrane and biomass combinations meet their limits:

Think here of filament bacteria, and especially oily and greasy contaminants. Even worse if those are synthetic. But in all honesty, conventional treatments would struggle here as well!

Conclusion on Membrane Bioreactors (MBRs)

You should by now better grasp the Membrane Bioreactor technology! If you want to even dig further, you shall listen to Graeme Pearce’s full interview.

Wastewater reuse is going to be a major challenge of tomorrow (remember, we’ve already addressed it here!). And obviously, it’s embedded in this podcast’s name: DON’T WASTE WATER!

Membrane Bioreactors are one of the most suited tools in the toolbox of modern wastewater treatment companies and operators, and after this deep dive, I’m pretty sure we all better know why.

Did we leave questions open? Please don’t hesitate to reach out!

3 thoughts on “MBR 101: What is a Membrane Bioreactor?”