with 🎙️ David Lloyd Owen, Managing Director of Envisager, Columnist for Global Water Intelligence, Advisor on several boards, and author of “Global Water Funding.”

💧 In his Global Water Funding book, David Lloyd Owen discusses global progress towards fulfilling SDG 6, proposes alternative solutions to lack of funding, and examines the reasons why countries are failing at implementing safe and sustainable water and sanitation for all.

This episode is part of my series on the UN SDG 6 and the path to reach it. Check it out! 😀

What we covered:

🍎 How the World is late not only on achieving SDG 6 but also on aligning to start working on it

🧮 How out of the three possible paths to solve the Global Water Funding challenge, only one is likely to happen

🍏 The ins and outs of Getting more Funds, Adopting adapted Water Tariffs and Doing More with Less

🌱 A breath of hope with Success Cases to replicate to set ourselves up to fulfill SDG 6

🧮 How numbers can be tricky, considering that only the ‘best pupils’ usually answer surveys and share data

🍎 How water is a political good that can serve much broader ambitions than just satisfy the thirst of people

🍏 How Denmark can be considered the international benchmark when it comes to water preservation and management

🍏 How Chile turned its entire Water Management on its head, thanks to political will – hence becoming another benchmark

💥 How the current level of Funding in the Water Sector not only fails to reach the SDG6 but also won’t allow maintaining current service levels

💥 How non-utility water will surpass utility water when it comes to Funding by the end of the current SDG cycle, and how that may trigger a negative spiral, ultimately becoming an existential threat

🍏 How the lowest hanging fruit may be cutting non-revenue water, currently representing 77 liters per day and capita in the World.

🍏 Private Vs. Public, Decentralized Treatments, Reuse Vs. Desalination, Populism, next writing topics… and much more!

🔥 … and of course, we concluded with the 𝙧𝙖𝙥𝙞𝙙 𝙛𝙞𝙧𝙚 𝙦𝙪𝙚𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨 🔥

Teaser: Achieving SDG 6

Resources:

➡️ Send your warm regards to David on LinkedIn

🔗 Check Envisager’s Website

🔗 Buy a copy of the Global Water Funding book

is on Linkedin ➡️

Infographic: Achieving SDG 6

Infographic-David-Lloyd-Owen-SDG-6-Global-Water-FundingTable of contents

- What we covered:

- Teaser: Achieving SDG 6

- Resources:

- Infographic: Achieving SDG 6

- Full Transcript:

- Introducing: David Lloyd Owen

- Introducing: the Global Water Funding Book

- SDG 6 – The challenge that shouldn’t be one

- SDG 6 builds upon MDG 7 (and ongoing programs since the 1980s)

- You only get data from the “Good Pupils”

- Three avenues to achieve SDG 6 by 2050 – assuming we will fail to do it by 2030

- First Path to SDG 6 – Get more Funding (unlikely)

- Second Path to SDG 6 – Improved Water Tariffs (sadly unlikely)

- We may not only fail SDG 6 but also miss the right funding to keep the current level of services

- Only country that realized how existential Water is align themselves towards SDG 6 (and beyond)

- Shall we really wait for the Climate Crisis to hit to invest into SDG 6?

- Third Path to SDG 6 – Do More with Less

- Getting creative to achieve SDG 6

- Utility – Community partnerships to pave the way towards SDG 6

- A low hanging fruit to finance SDG 6: cut the Non-Revenue Water

- Data, Information and Insights will generally help achieving SDG 6

- Does the Private Vs. Public debate play a role in achieving SDG 6?

- The role of decentralized approaches in achieving SDG 6

- The future weight of Reuse to address Water Scarcity

- To dig deeper – Read David’s Book!

- Rapid fire questions:

- Conclusion

- Other Episodes:

Full Transcript:

These are computer-generated, so expect some typos 🙂

Antoine Walter: Hi, David, welcome to the show.

David Lloyd Owen: Thanks for having me.

Antoine Walter: Well, I’m really excited to go to the deep dive today because I tell you I loved your book. So now I spoil what it’s all about. It’s about your global water funding book, but just swiftly before we go to the hard matter, let’s start, with a little tiny postcard.

So where are you right now? And what can you tell me about the place where you are?

David Lloyd Owen: I’m in my library right now. I’ve been working at home since 1999. So in that sense, COVID has been business as usual. And I live in a house on the edge of a small market town in west Wales called Newcastle Emlyn. I left London 22 years ago to bring up our children here!

Introducing: David Lloyd Owen

Antoine Walter: So that makes already two reasons for me to call you a visionary, but from your path, there’s something which is even more surprising. Let’s say I saw that you started in sustainable and environmental finance, I would say without spoiling your age long before it was hype. So can you guide us through your path?

David Lloyd Owen: True. I mean, I was funny enough. I was working for Paribas at the time and I was a technology analyst and covering mobile phones, telephones, and electronic equipment for equity investors. And it was the size of the Patty bowels big project was going to be infrastructure. And I told the head of research, well, my academic background was in the environment in ecology.

So why not put me onto water and waste management? And we did, and it took over from my original job. So 1999, there was one tiny little equity fund. There was a group of James Capel. Now part of HSBC and a, another group are now part of UBS. But in both cases, they didn’t really have a background. They were just simply analysts had been told, do your job.

Whereas I had a background and it was a sort of a coming of, beginning of the turning was circle. And I stayed an analyst on total in 1995. And ever since then, I’ve been a consultant.

David is an independent consultant and a columnist

Antoine Walter: So consultants on your own consultancy and columnists, if I’m right?

David Lloyd Owen: Yes. Envisager, which is a micro consultancy. And we have clients ranging from the world bank to company, wanting to know about possible markets for their technology.

And I write a column for global water intelligence every month, along with advising on the advisory board of Pictet water fund, which is the world’s first and largest equity fund dedicated to investing in water.

Introducing: the Global Water Funding Book

Antoine Walter: And when did you come up with that idea of writing your latest book? What was the trigger?

David Lloyd Owen: It actually goes back to when the OECD and 2011 asked me to try and come up with a number of what the costs for achieving universal access to safe water and safe sanitation would be.

That was in a sense that it was a quite lightly funded project, but I did it because it was just such an interesting one. And I was so horrified by the poor quality of information out there as one consultancy when reviewing all the estimates for the millennium development goals. But, it looked like most of these were done on the back of an envelope that also went back to two books.

I had published for Thomson Reuters. 2006 and 2009 on water finance, but that was not global. That was just looking at a selected number of companies and very much more on the thing, looking at where’s the opportunities and investments, where the opportunities for bonds debt facilities, et cetera, they all merged into this.

And then what happened was I went written a previous book on smart water, which was trying to give people an idea of the state of the art, about digital water that came out in 2018. This seemed a logical progression and it was the chance to completely revisit all the data generated previously and put it into one publication.

And it’s backed by this spreadsheet, which when I last looked at it and something like a quarter of a million data cells, so it was quite intensive.

SDG 6 – The challenge that shouldn’t be one

Antoine Walter: So we’ll go to the other, the depth of the analyzer of your book, but I’d like to start with the first chapter of your book because you open the book with a deep dive into what the state of the world currently is.

And a lot of let’s say background information, and you close the chapter by saying that that chapter should not exist, that you should not have to write that at this point in time, it should just be already old news. Why do you still have to write that chapter? What, what, what’s the main reason why it’s still not obvious all these elements that you share?

David Lloyd Owen: Well, putting it bluntly, the sustainable development goals, six for universal access to safe water and safe sanitation by 2030, I think the reasonable target for UN SDG 6 by 2030 would be that we have the capacity to start working on delivering it. It turns out for example, in the latest monitoring report, which came out a couple of weeks ago that a large number of countries still don’t even have an accepted definition of what safe water is, let alone a program to install it.

And various companies are still committing themselves just to installing basic or improved water, which is not. Well, this is all about basic will improve. Water has no definition of safety, freedom from contamination, freedom from bacteria, lead, arsenic, and so on and so forth. So you might get water coming out of your tap, but I wouldn’t recommend you drink it.

SDG 6 is late – at best

And it’s already been admitted that progress towards SDG 6 is running at a quarter of the level required. So the biggest challenge. And SDG 6 is the personnel or capacity and the staff on the ground in each country to be able to deliver the project and then the financial capacity, the funding required to deliver the project.

So really I believe the next few years is first of all, people admitting that they have not taken the process seriously until now. And don’t forget, this goes back to program being run since 1980. And secondly, how are they going to start addressing those gaps,

SDG 6 builds upon MDG 7 (and ongoing programs since the 1980s)

Antoine Walter: talking of these programs, which were run since the 1980s, what’s your show in this introduction is that there were three series of programs, SDGs being the third.

And if I get your rights, the previous programs were somehow achieved that somehow has to be defined, but there was also an increasing population which resulted in at the end of the day. Clearly no results in line with expectations.

David Lloyd Owen: That’s right. In terms of having three main problems with the prep programs before, first of all, there’s very much, I emphasis on monitoring people who live in formal settlements.

So the informal settlements. Very poorly monitored and considering how many people in developing economies live in informal settlements. That means that a great void in the data. Secondly, when you look at the various reports over the years and you cross-references and you realize the numbers have been rebased quite a lot how much confidence can we have in the numbers is again, open to debate.

And then really we’ve only started to look at capacities and capabilities and so on, in a critical manner, maybe since about 2011 and systematically since 2015. And in every case, you have to get the data, the information back from the countries. If they don’t wish to participate, all we can do is make guesses.

I kind of understand why a country would not wish to participate, but there are some quite odd regimes out.

You only get data from the “Good Pupils”

Antoine Walter: That’s something that’s roped me in your book is that you said times have some, some parts of the puzzle where you say there’s a dozen country, that filled the data. So you know that there’s a gap, which is about 90% of the data missing.

And you also regularly explain that probably the ones that answered are not the worst, because if you’re the good pupil you tend to answer. And I guess if you’re the bad pupil, you just skip the test..

David Lloyd Owen: That is a distinct problem. I mean, for example, one of the most useful sources of information we have is what’s called the blue book and the database, which underlines that IB net, which has helped manage by the world bank, which allows utilities to report back that whatever reporting criteria they wish to.

This isn’t a ‘developed’ Vs. ‘developing’ issue

So those in a sense, the ones which do report back outside the developing world, which too often disdains to join the project you know, there’s no participation from virtually any country in the EU or even in Britain. So that side you have to just set aside, but. Yes. What you realize is the better than utility, the more likely they are to participate.

So we have this core in a sense of companies, utilities, who are willing to participate, willing to disclose, willing to show their failings. And then underneath that you have rather like the iceberg, these massive utilities, which maybe they just, they very probably not only are poorly performing, they don’t know how they’re performing poorly performing.

And then they simply do not know how much water they deliver each day or how many customers they have. So, yes, in a sense, we have to base our understandings on the best data we can get. Irrespective of its failings.

Three avenues to achieve SDG 6 by 2050 – assuming we will fail to do it by 2030

Antoine Walter: So based on this best that I can get, you just mentioned that we are roughly doing one-quarter of what we should if we want to achieve SDG 6, which is our current goal for 2030.

And according to you, probably for 2050, my question here is you explore three avenues. The first is getting more funding. The second is getting a tariffication, which would cover the utility costs and more. And we’ll, we’ll dive a bit deeper into that in a second. And the third is making more with less.

How can we reduce the need for funding? Let’s start with the one, which in my opinion is going to be the fastest, getting more funds. That’s not right?

David Lloyd Owen: No. And it has to be said with climate change and with COVID, you have to understand that every government at the moment has, has to make hard decisions.

And water is always going to be down on the agenda politically for reasons which I can rationalize, but I cannot comprehend water is not politically important.

First Path to SDG 6 – Get more Funding (unlikely)

Antoine Walter: What would be your rationalization here?

David Lloyd Owen: I think because it’s taken for granted and one of the problems in particular, as you get governments, which don’t like to charge for water, of course, they’ve charged for water.

They charge for your taxes and your rates and so on, but they don’t charge. Secondly, that a number of governments, water is a, they useful thing to control and employees, a lot of people, it has a lot of influence and so on and so forth. So it’s something that they might just to keep to themselves. And finally, I fear the biggest challenge we have is the sheer scale of incomprehension about water.

When you look at telephones electricity, things like this, you can go an order. A handbook. We’ve probably come out every year, which will give you a systematic breakdown globally about these services. Some private entrepreneurs have tried to do something like that for water, but in reality, the quality of the data wouldn’t allow it for me.

One of the tree problems, there was a great expression used by Karen Bakker and. She called water an uncooperative commodity. Now this means that people are very reluctant to charge the appropriate price for water to reflect its worth. And so water is systemically undervalued, and because it’s not seen to be correctly valued the political world to fund it correctly is quite difficult to mobilize the particular problem that makes water unique is the fact that because of this low cost, it means that it’s economically very difficult normally to justify transferring water from one river basin to another.

And that means that every river basin is isolated and the sector is far, far more fragmented, even in a country like Britain, a relatively compact country. You have in England and Wales effectively 10 natural river basins and lots of stopper river basins within that. So that’s 6 million people per basin.

The scattered nature of Water doesn’t help

Now for electricity companies, you’d have far more people being served and so on and so forth. And when you look outside and where’s, the population densities are smaller, you know, America is served by 52,000 water utilities in France. It’s quite interesting. Cause it’s quite on one level. It’s quite consolidated.

But maybe 70% of the water sector is run by Suez, Veolia and Saur. But within that, you have something like my memories of me, rightly seven, seven to 10,000 individual municipal contracts. That means you’ve got an awful lot of small utilities with relatively limited management and relatively limited influence.

So the entire nature of water makes it particularly challenging for people to take it seriously and to consider the fundings seriously.

Second Path to SDG 6 – Improved Water Tariffs (sadly unlikely)

Antoine Walter: So that was the, let’s say idealistic avenue where we say the nice amount of funding, may be appearing now. And you’re just covered why that’s simply not happening. The one which I honestly don’t get is you deploy in your book, full rationale around the water tariffs, explaining what affordability means, because there is this right human rights to affordable water.

So we have to define what affordable is. And then you have this, this affordable tariffs. You have your reasonable affordable terrorists, and then you have the political terrorists and I don’t get why people don’t get that. They have to pay for the water at the right cost. If we are speaking here of 2.5 to 3% of their income, How did you calculate that affordability?

And let me do a four in one question, because I also read your, your column in GWI on, on the topic where you said that most of the time, when people are going to define affordability, they simply take what they’re currently paying. And they say, Hey, that’s affordable. 1 cents more is not. And 1 cent less is not enough.

So can you define affordable?

Defining ‘Affordability’

David Lloyd Owen: Oddly enough for the first time ever the world health organization started to consider what actually affordability means. And a study came out about a couple of months ago, trying to define affordability is until now it’s always just been taken to the magic figure. And really, it actually boils down to two numbers, one percentage of household income and two time.

So those without access to water, you have to factor in the time they would gain from having a top within their household. And generally speaking, one to 3% is the normal bandwidth for affordability, but you have to take into account. The costs of people are a lot more. Within a society. So you also have to take a look at the poorest 20% and then perhaps 5% of household income should be the limit of affordability.

But so

Antoine Walter: you, you took that bar, which is the reasonable limit for affordability, but in the book view, somehow divided still by two and say that is affordable tariff, but you still have another tariff, which is the political tariff, which is about twice lower

Factoring in the political nature of Water

David Lloyd Owen: Yes. Well, that is the problem is that there’s one thing which is a proper tariff.

And then there’s the other tariff, which the politicians might allow you to charge. And so went my point there being, especially with populism, for example, in Ireland, a few years ago, they tried to bring in tariffs and people were outraged. Of course, it was completely absurd because they’re already paying for their rates, their taxes.

And this is one of the absurdities about it. I personally think is far better to have all your costs coming through the tariffs where it’s visible and people know what they’re getting from their water, rather than money shuffling from one department to another and somehow or other the budget being made it much, much more transparent process.

It means that you know what you’re paying for your new, what you’re getting for, what you’re paying for. And one of the chief problems we have in water is engaging customers, engaging the public, and making them trust their water. So even in some extremely well-run utilities, you have large numbers of people still treating their water at home or boiling it.

Denmark: A lighthouse for successful water management

Maybe cause that’s quite perverse, but I have been told that one of the drivers for that is people think, well, our water is so cheap, so it can’t be clean. You take the other extreme though, in Denmark, which is the most expensive water in the world, you will find there. First of all, because it’s expensive, it’s used very carefully.

It’s created to an exceptional standard. Even the rainwater, which runs into a collection network goes through full tertiary treatment before it’s reintroduced back into the natural environment. And because they are paying for everything upfront in their tariffs. People know, yes, this is expensive, but we support it because we aren’t getting a sort of a switch.

We explicitly trust. And also because there’s a very high degree of disclosure in Denmark and every single utility gives all these performance metrics about him. And then people, again, they trust it. They said, okay, this is expensive, but I’m getting good value for money.

Why do “political tariffs” come in the way of SDG 6?

Antoine Walter: That’s the example you give in the book of that lager beer advertising, this reassuringly expensive.

So it’s playing on the Veblen goods. Somehow. What really puzzles me here is that you give so many good reasons to go for the right tariffs. And it’s not like rocket science, everybody gets that, but still the world spends 425 to $475 billion a year in water subsidies, which means at the end of the day, as you just said, it’s still taxpayer money.

So if we do it create somehow a virtuous circle, because if it’s more expensive than you cover for your cost and you can invest and you care much more about water and you trust much more water, because it is reassuringly expensive how can still all the politic decisions. Still be driven by, by this.

Pardon? My French stupid approach of political tariffs.

David Lloyd Owen: Oh, I wish I could give you a rational answer. She’s extraordinary rational. I mean, I remember once they’re the same passion debate, which is going on about the right to water, and actually the United Nations has a problem here because they have these special rapporteurs for water.

Affordable does not mean Free

And first of all, the rapporteurs have a phobia about the private sector. And so they’re, they comfortable with the status quo. Secondly, is the thing about the human right to water, which a lot of campaigners have tried to modify or hijack even by saying the human right to free water. You know, there’s still a very powerful, well-funded, aggressive lobby, which demands that people should get their water for nothing which A is inherently absurd and, and B free water free dysentery, free cholera.

You know, we can throw lots of things in with that free water if you want, but I wouldn’t want it. So, yes, as far as I’m concerned, the case is incontrovertible, but we do sit in there is just something irrational about water management,

Antoine Walter: bringing all that in maybe a bit more rational terms. Then, you cited a GWI study from 2011, which shows that the word spends $173 billion a year on CapEx and OPEX for municipal water and sanitation.

So far, it’s just a number, but your analysis is that is not even covering the maintenance of the current assets. So we’re not speaking of not achieving the SDG six. We are speaking of degradation of the quality of service over time because we are not able to cover for the cost. So how can we make the situation better if actually, we’re just spending not even enough to keep it as it is.

We may not only fail SDG 6 but also miss the right funding to keep the current level of services

David Lloyd Owen: First of all. I think it’s information because countries, for example, will say, yes, we have this many sewage treatment works. We treat the sewage, that many people, what they’re not telling us is how many of those sewage treatment works actually operate. How many have broken down? How many are performing to an unsatisfactory standard?

Take that across to all aspects of the water cycle. So what we need to do somehow is to inform the public. This is the state of play. This is what’s going on, and this is the reality. Are you happy with that reality or do you want to change it. Sometimes it is quite strange and particular governments have particular approaches.

A lighthouse towards SDG 6: the example of Chile

Chile had genuinely third-world water services in 1965.

Now their water services will happily stand comparison with most Northern European countries. They will have a 30 year complete top to bottom transformation of their services. So for example, there was 0% sewage treatment until the 1990s. Now it’s a hundred percent of which 78% is what I would call proper sewage treatment and water and sewerage universal zone and so forth there.

It was a government program. It was actually somewhat controversial because it was linked to privatization and the late stages, but a strong regulator, strong oversight, a strong amount of information, and the public got at demonstrably improved service. So I would imagine your average Chilean feels and sense of quite smug.

When they look over the Andes at their Argentina neighbor’s water, there is a highly political subject. And all I can say is that their services are of an order poorer..

Antoine Walter: Which makes me think that you’re advocating here for, for a system, which reminds me of what Ravid Levy on that microphone defined us, or explain us about how the water is managed in Israel with a national approach to water, and then case by case adaptation to the national approach, but always an overarching national approach, which kind of contradicts what you were saying at the beginning.

Only country that realized how existential Water is align themselves towards SDG 6 (and beyond)

That’s we have a water sector, which is scattered by nature by the river basins. So is it really something that can be adopted or is it because of the specific nature of, of Chile where with the Andes, maybe the geography is helping a bit..

David Lloyd Owen: Yes. I mean, there are certain countries where they have the politicians realized they face existential challenges when it comes to water.

So Israel, they realize now, here we are, we are building this country in an extremely hard area. And so Israel now leads the world, for example, on water reuse Singapore when it became into, yeah, from Malaysia in 1965, the Malaysian prime minister said if few step out of line with us on foreign policy or so on and so forth.

The example of Singapore

We reserve the right to turn the tap off. Because at that time, 70, 80% of Singapore’s water came across from Malaysia in a big pipe. Singapore’s aim now is by 2060 when its current contract runs with Malaysia runs out is to be completely self-sufficient in water. So water self-sufficiency and water security was from pretty well from independence day, a government priority.

And back in 1965, Singapore had, again, you know, an average, perfectly reasonable about inadequate water and wastewater infrastructure. Today. It has one of the world’s best because of concerted political will class educating the public, making sure the public was aware why we have to do it. So it’s

Antoine Walter: about realizing the emergency because you gave us two examples, Singapore, Israel, for them, it’s pressing.

If they don’t do anything about the water, they’re in big trouble. But when you look at the projections of where we will be lending in the next decades with water scarcity, rising population, climate change, the water stress is going to be a bit everywhere, which may then be if I’m very, with a bit of cynism, I could say it’s a positive thing.

Everybody’s going to realize how important water is. And maybe finally, we managed the water cycle.

Shall we really wait for the Climate Crisis to hit to invest into SDG 6?

David Lloyd Owen: It’s possible, but then I guess the warning there would be considered climate change. As far as I’m concerned, we have been in a climate crisis for three, possibly four decades. We’re now getting to the point where some politicians might actually acknowledge there’s a problem.

If we can take an action three decades ago, we would not be where we are today. But again, it’s taking big, difficult decisions. And of course the whole thing about politics is you’re thinking about the next election, or if you’re a dictatorship, you’re thinking about your next mistress, your next palace.

You’re not thinking about things like water, climate change infrastructure, the big picture. And there’s a a lack of understanding that difficult things have to be done. Long-term projects have to be completed.

Antoine Walter: What struck me by reading your book, is that what you just explained about the importance of having this global approach as it is not present

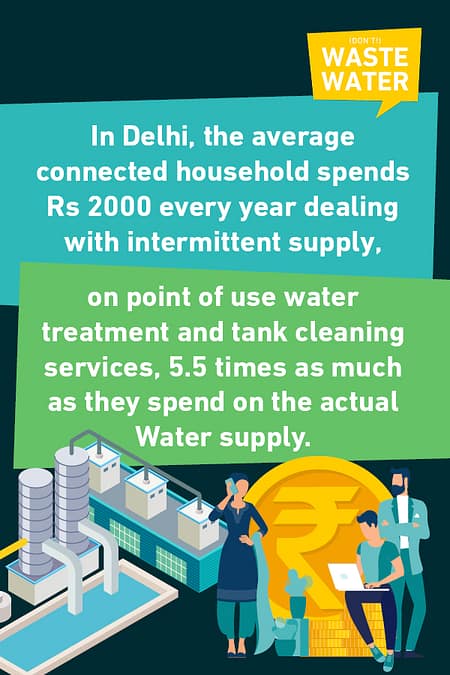

Non-Utility Water may become a (dangerous) alternative

Well, there is alternative solutions which are popping out and these alternative solution is that, well, if you don’t get the water from the utility, maybe you can get the water from somewhere else. And that’s somewhere else, maybe point of use, point of entry, as you describe it, but also bottled water, which is clearly the dominant player there.

And what you show is that there is a switch in power there because by the end of our SDG period, well, non utility water will attract more funding than utility water, but more funding for less water as well. So if we’re able to afford non-utility water, can’t we just, I mean, that is now very, very, very theoretical thinking, but can we not just not derive that money and fund utility water, which is more efficient at the.

David Lloyd Owen: Yes, it’s one of the great ironies. I mean, apparently more money has spent now on bottled water in California than on tap water. And of course, one of the strange things is bottled water. For example, in America is not subject to regulation. So if you want to get sick drink, bottled water, if you want healthy water, have a properly funded, properly managed utility.

The, the warning there is that if utilities are unable to deliver water, which people trust, then people will just have to use we’ll use alternative sources and ultimately you start to create a negative spiral because then if that means they’re spending their money on other sources of water, then there’s still less funding available to the utility.

So you have to break that cycle. And again, you have to acknowledge, they have to acknowledge that this is an existential threat.

Third Path to SDG 6 – Do More with Less

Antoine Walter: So so far, it’s not very positive. What we’re discussing. We’ve seen that from the two path, getting more money is not happening. Getting affordable tariffs is not happening either.

So that leaves us with the third and last option, which is to do more with less and actually doing more with less. As we shortly alluded to with the utilities, not getting the money, they need to cover the infrastructure. What that’s another figure which you share, which shows that their free cash flow went from 121% of their operating costs.

Two, 108% of their operating costs in the decade. So between 2000, 2010, what would be the right target in terms of percentage of the operating cost that they shall reach in order to, to sustain what they’re doing and to be able to have a bit of investment capacity.

David Lloyd Owen: It all depends on how much capital work you are having to do.

How much of its operating costs shall a Utility cover to be financially self-sufficient?

And there, there are two classic definitions of water tariffs. There’s the full cost recovery where you cover 100% of your operating terrorists and you have enough money over that to fund all your capital work. That means you might be paying some of it straight up now, and you might be raising debt and paying the interest on that date and debt and repaying that debt over a period of time, then you have sustainable cost recovery where you cover all your operating costs, but you, your capital costs will be from your surplus and from grounds and so on and aid.

And what happens is for developing countries to try and make water more affordable, where they do have alternative sources of funding. Generally speaking, Be something like 140 to 160% of your operating costs. Now the caveat here, and it is a big caveat is let’s say, just imagine SDG six succeeds at some point in the future, that means we’re going to have a great deal, more assets.

I mean, use it during the past. That means you’ve got a great deal, more to operate and maintain and manage and renew and upgrade and replace. So of course the more you achieve, the more you have more assets, you will have to manage, but generally speaking, 140 to 160% looks a sensible sort of figure, unless you’re particularly capital intensive phase and maybe you have to pay extra.

Getting creative to achieve SDG 6

Antoine Walter: So that means that as we saw that it’s not going to be higher in terms of income, we have to reduce the cost and you give several. Ways to reduce the cost to say, we have this 108% on average. If you want to bring it to 140 to 160, as you just explained, as you cannot move with the total let’s play with the divider and playing with the divider may take many shapes and you, you explore several avenues.

There’s one that comes quite regularly in the book. I mean, it’s several different points in chapters. It’s working with local workers and local. Yeah. To, to have kind of a partnership between the utility and the local worker. You give us several examples. You give a study from the world health organization.

Examples from India, WHO studies or Bolivia

You give an example for, from India, but the one that’s stroke me. The most I have to say is, is your Suez case study in La Paz, Bolivia, where you show that they were literally cutting the costs in terms of, of household connections by using local labor and cutting the cost, doesn’t just mean you have less cost.

It means more connections for the same amount of money. And you also showed something which, which reflects with what you were saying earlier, that there’s a 60% increase in the community support. So people take ownership, which I would coin, like, you know, the, the Ikea effect when you’re building an Ikea shelf, all of a sudden it’s much more beautiful than it really is.

Just because you build it with your own hands. What I’d like to understand here is what is this local labor? How does that work? What do they actually do?

David Lloyd Owen: It would be in case of, let’s say you’re wishing to lay a sewer scheme to an unconnected area. The you’d get in engineers and so on and so forth, who would teach people, tell me what they need to do.

Utility – Community partnerships to pave the way towards SDG 6

So what the community is coming is committing is time, time, which would normally be paid for by external contractors and so on and so forth over the digging, the layering and so on and so forth. All that manual labor, which normally would have to be paid for externally is now being donated by the community and towards the project.

And again, this has been very much the approach taken in Pakistan and in India. And as you say, the new, because you’re donating time and effort and sweat into a project, you acquire a sense of ownership. Even, even if it has been managed by somebody else you can say, right. Well, we now have a top and a laboratory which works in our house and we have safe water.

My children are healthy, nobody has to waste time, collecting water, or going out to a latrine block or anything. And that’s being done on my own back that in a sentence is okay.

Antoine Walter: You also share with your, your, your case study is around. I think it was India that the quality is even better because the latrines built by contractor I’ve built, I guess, to cost.

Whereas if you’re building your own laterals for your village or for your community, then all of a sudden they’re much better, which means they’re also more used. So there’s different levels of acceptance, which sounds like a perfect way to go.

Involving local communities has several welcome side effects

David Lloyd Owen: Yes, it does a lot of good case studies. And of course it does depend on things.

You’ve got to have the right equipment and make sure that it’s the best equipment for the job. They’re most appropriate equipment for the job. And you need the right supervision to make sure that everything is done correctly, but because of that sense of ownership, you want to do the job well. Whereas a contractor, maybe you’re not just rather more interested in getting the job done, ticking a box and walking away with a nice big fat check.

A low hanging fruit to finance SDG 6: cut the Non-Revenue Water

Antoine Walter: So that is a way to cut at least connection costs and also to have these welcome side effects of the additional ownership and quality and long-term benefits. Then there’s these very, very low hanging fruit or that that’s the way I perceive it, at least, which is just non-revenue water. And do you show that non-revenue water account for 77 liters per capita and per day in the world, which is huge when you think of it, when you see that there are initiatives like the 50 liter home in the, in the Netherlands, which, Paul O’Callaghan alluded to when we were having the discussion on that, on that microphone.

So in place of the words, you could be able to, to run a full house with 50 liters, and we are still on average wasting 77 liters in non-revenue water. So I don’t have the figure in mind right now, but I think you said something like 58 billions or some, correct? My figure here, we would still work, who could save every year by reducing this non-revenue water.

So what are we doing?

David Lloyd Owen: It’s a really interesting question. And funny enough, something happened since I wrote the book and there was this wonderful talk a few months ago by a man working at Thames water London. And when they started for the first time to get the data from the smart meter rollout program.

Smart Metering helps to understand what’s happening

So instead of getting a meter reading, if they ever had one in the first place, every six months, and now dealing with real-time data, 24 hours a day, the average. Amount of water remained the same. It was still at around 140 liters per person per day. But what they discovered is that most people were using 120 and there were a small number.

It was in between two and 600 a day. The reason being quite often that they had a leak inside their house. And so the one thing that I said, okay, we’ve now got the real granular data. What we have here is 30 to 50,000 people who need to be contacted fast. So their original prime program was going to be a general.

Process of engagement with everybody in the Thames region program, too. We have an emergency get in touch with all these people who are using the exceptional border and say, look, there’s something wrong about your water usage. And it almost certainly is costing you money. So they did that and things might start to change for the better.

Now, the thing is that there are two types of non-revenue water. That’s the water, which is lost within the house, which is up to 30% of all lost water. And then there’s a water lost within the network. Again, once you start having metering, you can see and especially smart meter, you can start getting a real handle on how much water is being introduced to the network.

Collecting data at house connection and network levels

How much is the customer consuming and therefore what has being lost in the system. From there, you can start looking at each district and saying, okay, this is the bad one. And from there, we’re now seeing genuinely. Interesting leakage protection technologies emerge. So for example, traditionally, you knew when there was a leak when suddenly water spurting up in the street, or even worse when a building collapses, because the leak has been going along, it’s been washing all the water, the soil underneath the house, and all of a sudden the foundation is sitting on water or air.

That’s a real problem in some places. So first thing to do is with real leakage detection is to be able to make a hierarchy of leaks at the bottom. You have the insidious little localized leak. Yes is losing water, but it’s quite a low amount and it’s a low priority. If on the other hand, you’re going to do program upgrades and so on and so forth.

It’s on there. Then you have your standard leak. Okay. That’s a medium priority. You know, we started a full rectification program and then finally you identify which ones, even though there’s no visible manifestation of this, I actually bursts and say, okay, that’s an emergency. We deal with that. So you can, for the first time ever, you can start having an informed hierarchy of responses to leakage and compared with the cost of the assets themselves smart metering, smart leakage detection, and so on is remarkably creep.

Balancing pressures on the networks

So it is possible. Another technology technique is pressure optimization. Because the more pressure you have within a network, the more water gets forced out through leaks. If you can have the ideal pressure throughout the network, that can cut leaks by 20 to 50%. So again, it’s coming to get into an acceptable amount of leakage.

It’s very rad. There’s no such thing as zero leakage and some of the best systems in the world that three to 5%, I think anything below 10% is good.

Antoine Walter: If it gets you right there, it boils down to having the right data. Because as soon as you start having these smart meters and also maybe smart pressure and regulation on, on the network, you, you give some examples in the book around that swiftly you, you, you have a better insight and if you have better insight, then you know where to act.

Data, Information and Insights will generally help achieving SDG 6

And of course you can put priorities and start way it brings the most you’re right. That, that may well be the first. Positive effect and largest positive effect of the SDG 6 to have this, this better view, this better overview, better understanding of data. When you say that, w how important is this, this data?

And when you speak of data, is it’s linked to the digitization, or is there more to it?

David Lloyd Owen: It is simply crucial. There’s the old Maxim what you cannot measure, you cannot manage, manage. And so, yes, you have to know what on earth your assets are and how let alone, how they are performing. If you can start getting on top of that, we move into the era of informed decision-making where as, too often in the past water has been, even when you’ve got good engineers out there, the information they’re given means that they’ve been able to defer more than inspired guests.

Okay to come back, for example, on a leakage, as an example, a traditional technology sometimes meant that you’ve got an idea that there was a burst within plus or minus 20 to 50 meters. Now you can get it down to a couple of meters. So instead of having to dig up a whole road, bam, go straight to where the trouble is sorted out minimum disruption compared to the old way and much less cost and right up to the macro level.

Examples from the privatized UK water sector

So that governments can actually understand what are the problems and how can we respond to them. And yeah, if you take something like in Britain, in England and Wales back when water was privatized in 1989, because all we’re billing was done by how much your house cost, no one bothered to meter. Because no one bothered to meter, there was no, no idea about leakage, leakage, only a merge I’m on two years or so often privatization.

And you said that there was this absence of information. This is information about things that matter things that sure are important. So what we would hope to do is get a virtuous spiral, more information, better decisions. Therefore we know better what we need information about even more informed decisions and so on and so forth.

And then you’d look at some of the really well managed utilities, especially for example, Singapore, and some of the Northern European utilities. They are running a tight ship.

Does the Private Vs. Public debate play a role in achieving SDG 6?

Antoine Walter: What you just said about these consequences of privatization in, in the UK leads me to a very subjective question. I was just wondering, I know that you write in the book, it’s not about private versus public swamp.

I’m not trying to trick you here, but still I wasn’t the impression which was bit renewed in our discussion. Just spin it to you when you were mentioning how Sheila went from bottom to top, and that the best possible scenario is private management of water under a tight watch of the public.

Right. It’s an interesting one.

David Lloyd Owen: I would actually call myself a critical friend of the private sector. I believe where private participation can, can demonstrably do better than the status quo. It should be considered where it demonstrably cannot. It should not be. And this is quite an interesting one here. For example, in Singapore, public utilities boards, remit is.

They do everything. And of course it’s completely government control. However, if a external actor can run a facility for less, especially for new assets, then it goes out. So for example, some major new wastewater treatment and reclamation plants and desalination plans are being run on 30 year or so concessions, of course the assets there will ultimately revert back into the hands of the government.

It’s all about shades of Grey…

You’re looking back. I try, I do wonder if when they privatized the sector in England and Wales, what they should’ve done is not privatized the assets, but privatized the management, because what you now have is things like pension funds, controlling water assets, which. In the case of monitoring utilities and Britain has been problematic to say the least, because there’s a conflict of interests whose interest are really honestly, I think so if in Britain let’s say all what had happened is that you’d had a comprehensive concession award, but 30 years apart from anything at the end of that 30 years, there’s a mighty incentive for the concession holder to show that they performed really strongly and therefore they deserve another 30 years.

And if they’ve actually. Perform poorly. Sorry, gentlemen, good by privatization in the early days was hit and miss. And as one didn’t think they will drive followed, trying to follow the fate of lots of contracts from till about 2000, 2005. Quite a high number of contracts were being lost because especially the immune Tasmania or the government said, no, this is unsatisfactory.

… and a right sense of ownership

We’re taking it back. The worst worst example was the contract, which lasted four days. Whereas La Paz and Alto in Bolivia was very much a political reappropriation of the assets in the last 10 years or so. On the other hand, the great majority of contracts which have ended have been at their agreed expiry date.

There was a lot of pretty questionable behavior in the early days. And one of the interesting things is that you have these days far more local management, local involvement, rather than half a dozen countries, bestriding the globe. So in attention, a privatization or really private public participation has matured somewhat.

I can easily believe certainly of the urban population there’s scope. For 25, 30% of the population being served by the private sector, but there’ll be a lot of areas where quite simply, now there’s a leap too far. You do want the private sector be involved in specialist services. And of course in the provision of support services and technology and so on and so forth, but there’ll be launched waves of the water sector where I suspect the private sector can’t bring enough to the table to justify being involved.

The role of decentralized approaches in achieving SDG 6

Antoine Walter: I would have a ton more questions, but I’ll take two last ones in that, in that deep dive and just drawing on what you just said. I was wondering if the right size of stuff would not be this enormous. Utts like, like we have you also address bone of views, point of entry in the book and you addressed the centralized treatments.

And I’m wondering if the right size, which would bring people in to have their ownership. As we discussed minutes ago, which would draw private companies in, at a sizeable chunk of a market and still deliver some scale effects would be the decentralized size. What’s your, your subjective opinion.

David Lloyd Owen: That can be quite often a lot of scope for, especially away from big cities, possibly more decentralized and even D possibly in a community owned systems.

Micro-Utility, Point of Entry, Point of Use

Point of use is very much depends on the circumstances and where we have on the satisfactory services. And it’s going to be years or even decades before they all satisfactory. Point of views is an extremely important halfway house, because that means at least people get access to safe water. In our case, we lived on a farm for 19 years before moving to this house and we had our water from a spring and they’ve lived rather rough and ready network.

So in those days we had to just treat it cause the water very, very lightly because the water was somewhat acidic and grow to the pipes. But when we moved or something. How strange the water tasted cause we were simply, weren’t used to chlorine. So the, the one thing we have done is we’ve been put in a PO you chlorine remover in our kitchen and it just purely for aesthetic reasons and that sort of thing.

There’s always a case for that. It all really depends on having lots and lots of pipes, Lin, linking communities up and so on and so forth may have to higher costs rainy as a base. It’s comparing the cost of little treatment, works against the constant of lots of piping. And I think that what is crucial here is that one size does not fit all every country.

Every society, every river basin has its characteristics and we need to be flexible. We need to be creative to look for that elusive, but attainable balance.

The future weight of Reuse to address Water Scarcity

Antoine Walter: I’ll take as promised the last question in that deep dive and has to do with this a bit with this decentralized aspect and closing the loop.

Actually, you give a figure about reuse in the book where you say that you, you see reuse taking four times the importance of dissemination to cope with the, the water stress. And I was wondering there’s a lot of objective data to support that assertion, but how do you factor in the acceptance of.

David Lloyd Owen: It’s very difficult, very difficult.

Indeed. One thing you can tell them is wind hike in Namibia. They have been now running a water reuse plant for direct straight back to the customer water reuse. And as far as I know, they had never encountered a problem for it. The water has genuinely potable. The problem is, is what you might call the yuck factor.

The sad story of “Poowomba”

So in Australia, for example, there was this town hall tomorrow where they wanted to have water reuse, but the populace that we don’t want to be known as Pooler era. Congratulations, they more or less did was they got lots of money from everybody and they put it in the middle of the town and they set it on fire.

So instead of having an economical, effective water system with water reuse, incorporated, I spent money wasted 165 million Australian dollars pumping and piping the water in from a distance source. Congratulations, that’s populism very likely the most pragmatic middle way is for example, what’s being done in Singapore, where they make use first of all of in direct non-potable.

That means all the industrial customers now expected to use reclaimed water for their process water and so on and so forth. And then they have indirect potable whereby they, even though the water is completely clear. Instead of putting it back into the distribution network, they put it into reservoirs where it is treated again in engineering terms, this is called the magic mile.

Reuse is already there, it’s just a matter of reducing the size of the loop

There’s something about releasing effluent or whatever into a river, and then picking it up a mile down or keyed one and a half kilo down downstream and treating it and putting back into the network. And everyone says, that’s perfect. There are various cases around the world, but I think in London, water can be taken out and treated and put back in again, five or six times down the length of the tendons in an extreme case.

And something like the Rhine long continental river, you are talking about water, which is being around a bit. So I think it’s going to be always be quite hard to a effective case for direct potable, even though the case out that exists. However generally speaking. Industrial municipal and so on and so forth.

Use of water is usually two to three times higher than it is for domestic water. And that means that all the water that is reclaimed from domestic sewage and so on so forth could simply be applied to non-potable users with a little imagination. And so it’s quite likely that we can elegantly sidestep the problem in many cases.

To dig deeper – Read David’s Book!

Antoine Walter: Well, I think we scratched the surface of your book. Honestly, we are one hour in roughly and steel. I mean, it’s a wealth of information. So if anyone wanted to go a bit more in depth, there are so many facts figures. I mean, the pool Womba story is only one of the, of the several shame story that you have in the book, but there’s also very cool story.

Again, quote, for instance, the New York city story, where they leveraged a bit of, let’s say system thinking instead of jumping to conclusion, they thought of, of Riverbed sense. So just to just say that there are several examples that we, we, we can not just take right now for time reasons, but for anyone wanting to add to go more in depth, I’d recommend reading your, your, your global water funding book.

And if it’s fun with your proposal to switch for the rapid fire questions to close our discussion,

Rapid fire questions:

Antoine Walter: So in that last segment, I have short questions aiming for short answers. If you need more time, I’m not cutting the microphone. But my first question is going to be

What is the most exciting project you’ve been working on and why?

David Lloyd Owen: In a sense, it was the one route I doing well with the world bank on capital efficiency, because someone was paying me to look for examples where we can save money by create thinking creatively about how we get goods and put them together.

What’s the favorite part of your current job?

David Lloyd Owen: It’s probably looking for new ideas, especially in academe. So for example, a few weeks ago, a paper came out in nature suggesting a new form of water treatment, potentially, which would make a variant of hydrogen peroxide, which they estimate to be. 10 to the power of seven to 10 to power of eight, more effective than chlorination and leaves, no residues.

So that’s the theory. If the reality can be as hundredth, as good as that, we are transforming water

Antoine Walter: weather, aside from that very promising ones.

What is the trend to watch out in the water industry?

David Lloyd Owen: I think, and I’ve been saying this for a few years, I’m afraid, but keep eye on smart water as it starts to move from being clever ideas and exciting talks at conferences into delivering practical benefits, especially.

And most importantly, when individual innovations are knitted together into a coherent and more effective whole so incremental savings, incremental improvements, all of a sudden start jelling into very large improvement.

What’s the thing you care about the most when you’re working on a new project and what is the one you care the least?

David Lloyd Owen: The most is trying to get the data and trying to make a case for looking at things with a new pair of eyes, the least is when you can send the project in you get the money and you get no feedback. So in a sense you feel you’ve just been there. You’ve been paid just to tick boxes and say, oh yes, we employed a consultant to look at this.

And that is that’s yes. You want to know you’ve got it right? Or you got it wrong.

Do you have sources to recommend to keep up with the water and wastewater market trends?

David Lloyd Owen: I’ll have to declare an interest here. Global water intelligence magazine is definitely one of the best. And another one is it’s on the web and it’s free.

It’s called smart water magazine. And every day does power off a dozen, a dozen news stories. And again, they are quite good at keeping a nose out for what the journals are publishing.

Antoine Walter: When we were preparing for that interview in our extended, you mentioned that you’re working on your next book. What will it be about?

David Lloyd Owen: It’s very much a, well, put it this way. I have an agent and he wants me to prepare them and material to his satisfaction to send to the publisher. But the essence of the book is going to be about rethinking the whole of water and trying to transcend a view of the water is just an endless series of obstacles and barriers.

And to what happens when we really start to think optimistically. So it’s not, what are we faced with and what we can do.

Towards David’s next book

Antoine Walter: What do you have when I worked for me when you are on the media tour for that next book.

David Lloyd Owen: Oh, watching the space. But I would, I would hope I’m, I’m hoping it will come out next year because I wrote my first book on water in 2012.

And in a sentence, one part of the book would be the journey of my understanding 10 years.

Antoine Walter: So I I’ll make, make sure I’m available in 2022 to, to have you on that microphone. Last question. Would you have someone to recommend me that I should definitely invite as soon as possible?

David Lloyd Owen: Oh, I certainly would. I think it’s good value for money or funny enough, if you want us to consultant to produce a study like that for you you would be paying tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds.

So for tens of pounds here it is global water funding, innovation and efficiency as enablers for safe, secure, and affordable supplies, actual friendly Amazon.

Conclusion

Antoine Walter: Well, David has been a pleasure. I think we make a good tour. And I really subscribed to your recommendation to read that book. I think it’s a, it’s an eye opener to many, many aspects of, of, of this very trendy SDG six, but sometimes yeah.

Overlooked. I have to say when a compared with what you write about it. So I hope to have you again for your next book and thanks to it up.

David Lloyd Owen: It’d be a pleasure! Thank you.

7 thoughts on “3 Paths to Reach SDG 6 by 2050: All Our Hopes are on #3!”