Each of the past ten years, 15’000 pumps installed by water charities in Sub-Saharan Africa went out of order. This “build, break and rebuild” approach represents a $5 billion wasted investment in a region, where 400 million people lack access to safe water.

A fatality? Not at all! Let’s review the causes, and propose three solutions.

This is part of my deep dive into the 6 Decisive Things you shall know about the UN SDG 6

Table of contents

- Water Charities’ doom: Build, Break and Rebuild

- The problem with Water Charities’ procurement

- Water Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: an Increasing Issue

- Learning from Sanitation efforts in Rural India

- Tool 1: Community Involvement

- Does Safe Water pay for itself?

- Problem: Water is Capital Intensive

- Introducing: Muhammad Yunus

- Tool 2: Microcredit

- Why “Credit” and not “Donation” like Water Charities usually do?

- Microcredit shifts the challenge

- Tool 3: Impact Investing

- Conclusion: the Future of Water Charities?

Water Charities’ doom: Build, Break and Rebuild

What do you think: how many water pumps are abandoned in Africa as we speak?

Paul van Beers has been working for Universities, Consultancies, the World Bank, Governments, and international NGOs.

And that is exactly why he initiated the FairWater Foundation. (Let me explain.)

In 1985, when he first arrived in Burkina Faso, he got involved in creating 500 water points in rural communities. Yet, what he discovered when returning to these communities sometime later shocked him.

He’d expected them to strive around the pumps that finally brought water closer to their homes in a safe manner.

But he instead discovered that women had returned to their former pain of walking distances to get water of questionable quality from faraway rivers!

The cold, sad truth was that the pumps were simply out of order.

There are 300’000 abandoned pumps in Sub-Saharan Africa

In his “Global Water Funding” book, David Lloyd Owen synthesizes multiple studies on the topic. As he points out, handpumps deployed by NGOs in Africa last less than five years.

As a result, in the mid-2000s, 36% of about 350’000 installed pumps in Sub-Saharan Africa were not functioning. By 2010, there were 150’000 abandoned pumps in Africa. And by Paul van Beers’ count, that number escalated to 300’000 out-of-order pumps today.

That’s about $5 billion in wasted investments, all from Water Charities that I trust had deployed that money with the purest intentions there is!

So why the debacle? In his book, still, David Lloyd Owen calls it the “build, breakdown and re-build approach.” If you ask them, many will blame it on the local communities that fail to maintain the equipment they receive. But if you scratch beneath that surface, there’s another story that reveals.

The problem with Water Charities’ procurement

Until 2006, the US Agency for International Development’s website proudly boasted how “the principal beneficiary of America’s foreign assistance programs had always been the United States.”

Why so? Well, simply because all along the Water Decade – not the one we’re in, the one that happened in the 1980s, history tends to repeat – US law required USAID to use American contractors for most development works.

As a result, 80% of contracts and grants went directly to American firms.

What’s wrong with that, after all? It sounds like a clever use of a virtuous cycle. You support the economy while doing good!

The impossible maintenance of donated water pumps

But here’s the catch. Even the best piece of American furniture will eventually break at some point in time. And when local communities need to repair, they will also have to import spare parts from America, which will become an unbearable cost. And as a result, the pump will be abandoned.

On top of this, maintenance is a skill that requires a knowledge transfer, another step that often goes missing in the approach where a foreign body comes and installs a turnkey solution.

Water Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: an Increasing Issue

Hence, we have a problem: according to UNICEF and the World Health Organization, 80% of the people in the World still lacking basic drinking water services live in rural areas, and over half of them sit in Sub-Saharan Africa alone.

And despite the World’s efforts over the past decades and the global situation getting somehow better, the number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa that have to endure a roundtrip for water collection that lasts over half an hour doubled between the years 2000 and 2017.

But if Water Charities parachuting pumps in those areas don’t solve the issue, what does?

Well, the pooping behavior of rural Indian communities may give us the first hint.

Learning from Sanitation efforts in Rural India

In a 2018 paper, Aashish Gupta from the University of Pennsylvania studied the changes in open defecation in rural north India.

Over the course of 5 years, access to sanitation had increased from 38% to 94% in the region through a $31 billion investment in 111 million latrines.

Yet, three successive studies showed that the open defecation practice was hardly reduced at all between 2014 and 2018. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh, 40% of the households with latrines simply didn’t use them.

As David Lloyd Owen tells in his book, the catch was straightforward.

Latrines of insufficient quality…

A Water Aid study showed that only one-third of the newly installed latrines would be sustainably safe. Another third already needed improvement after only a couple years of service. And the third third was not fit for purpose at all.

The building of these latrines had widely been attributed to large contractors that repeated a standardized design-to-cost approach.

As a result, pit designs sometimes made it impossible to empty them, other times prohibitively expensive. The icing on that cake – not sure about this expression in that context – was that pits were undersized and needed very close emptyings in time.

Now, in the middle of all that mud – again… – Aashish Gupta digs out a revealing data. One portion of the new latrines was seeing a much higher use rate and hence actually ended open defecation in those households.

… except when built by local communities!

What was their kick? Well, they had been directly built by the villagers.

In his book, David shares further examples of that approach, from the wastewater condominiums in Brazil to the new house connections to drinking water in Bolivia. And that sounds like an up-and-coming prospect.

The idea is generally that local communities will provide and donate their labor, while utility, government, or large private entities source the materials.

Now, to my knowledge, that approach has never been successfully deployed on a large scale in Sub-Saharan Africa. I might be wrong, and I’d honestly be happy to be! If that’s the case, just drop me a comment.

But one of my African students shared with me some stories of a trial the utility she’s working for had conducted in Nigeria. And the results were quite negative, with sub-urbs transforming into small baronies, which was just displacing the problem, if not worsening it.

Indeed, that may have much to do with this fact, Christopher Gasson shared on my podcast microphone.

Less than 20 utilities across the 46 sub-Saharan countries are seen as structurally solid enough to partner with international development programs.

And it sounds like a safe bet to assume that none of them actually operates in the rural parts of the region I mentioned earlier.

Tool 1: Community Involvement

Yet, I feel like we’ve partially solved the riddle. Community involvement is the first key ingredient of the path to success we have to find.

The second hint in that journey actually also comes from that same podcast interview with Christopher Gasson. (In case you don’t know him, Christopher leads Global Water Intelligence.)

Some time ago, GWI conducted a study to answer this question:

Does Safe Water pay for itself?

When you think of it, unsafe water is quite expensive. First, it carries diseases that can be deathly or, to a lesser extreme, prevent people from working.

I think we’ve unfortunately already covered all the variations of that terrible statistic: every year, about 300’000 children under five die from diarrhea linked to unsafe water sources.

And I won’t open a sidetrack here, but the next time you see footage of the horrors currently happening in Ukraine, think of that UNICEF report. Children under five in warzones are 20 times more likely to die from waterborne illnesses than from violence.

Waterborne diseases can have less extreme consequences than death yet still prevent people from working. It was estimated in 2002 that 9.1% of all disability-adjusted life years stemmed from deficient water.

Unsafe Water costs the world $300 billion a year

But that’s not the only reason why unsafe water is expensive. We also have to account for what Matt Damon and Gary White qualify in their book – the Worth of Water – of water’s “coping costs.”

First, there’s the time spent walking for water. That’s a time when, almost always women, don’t work, study or add any value in their lives, beyond acting as a human pipe.

Then, there’s this staggering fact Gary White underlines in the book: “people living in poverty pay absurd prices for water.”

For instance, water from a tanker is 50 times more expensive than water from a tap. Families without toilets pay to access public latrines when they don’t simply go to bathrooms “in the open,” hence polluting the very water source they rely on. Which later means medical bills.

When you add up all these coping expenses, they cost the World about $300 billion every year!

The cost of inaction is higher than the cost of doing good

But wait, we know how much it would cost to provide water and sanitation for all and achieve the UN SDG 6. Development reports agree on a figure of $114 billion.

Hence, and as GWI also concluded, we clearly see that, yes, safe water pays for itself!

Unsafe water costs $300 billion, and safe water $114 billion. That’s a no-brainer, right?

Well, not really. The challenge is that you have to pay upfront to get the life quality improvement down the line.

Problem: Water is Capital Intensive

In a central utility approach, you have to invest 7-8 dollars straight for 1$ of recurring revenue at best. That’s a high financial risk, especially when you have a limited guarantee to ever get paid back. We’ve already seen how water is a political good.

So, safe water pays for itself, but only if someone dares to invest first.

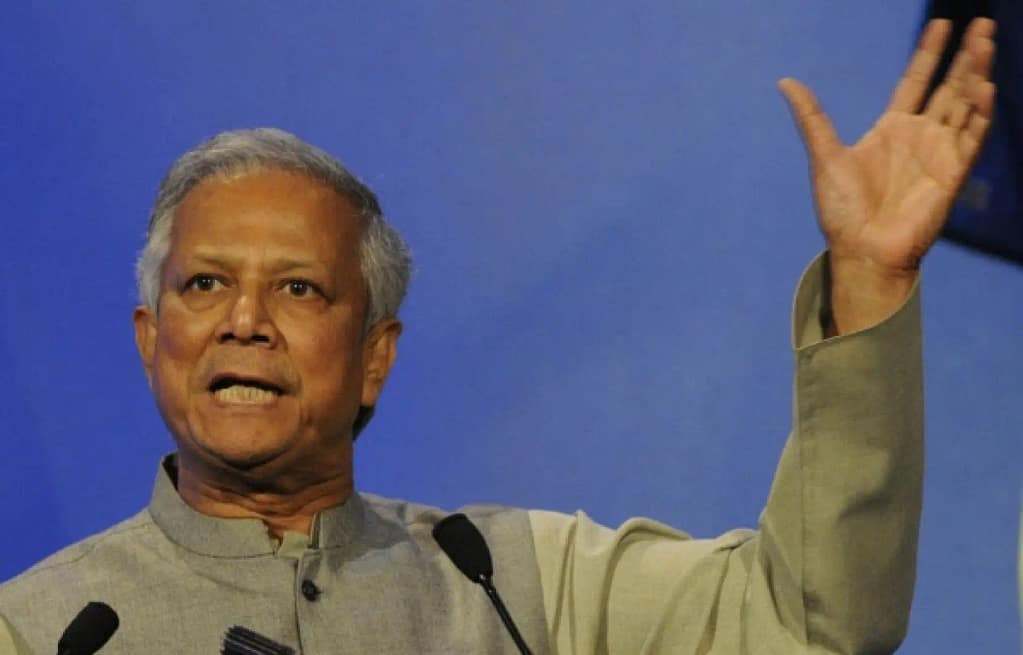

I guess that’s the point in time where I need to take 40 seconds to talk about Muhammad Yunus.

Introducing: Muhammad Yunus

In 1976, Yunus, who would later win the Nobel peace prize, visited a village in southern Bangladesh. He met with a craftswoman who lived in a devil’s circle. Her business earned her just enough to sustain itself but not enough to take her out of poverty.

As she wasn’t alone in that case in the village, Yunus addressed the whole group. He asked them how much money they would need to break free from the traders that maintained them in this state of semi-slavery.

It turned out that the entire village needed just 27 dollars to do so, so the economist reached for his purse. But he didn’t give the villagers the money. Instead, he lent it to them with no interest.

One year later, the forty-two borrowers had all repaid their loans, and Muhammad Yunus had proven a point: microcredit is an incredible development lever.

The reason why I’m mentioning Muhammad Yunus is that it provides us with the very tool we were looking for.

Tool 2: Microcredit

We’ve seen that safe water pays for itself, so we know that in the long run, the cost to do good is lower than the cost of inaction. So credit allows us to break the elephant into pieces, and microcredit enables us to merge this second tool with the first one: community involvement.

Now, people lacking access to water are no longer on the receiving end of a foreign charity. They become the heroes of their journey.

Oh, and before you ask, is that 100% repayment rate, Muhammad Yunus experienced the exception?

A Water Charity’s take at microcredit: WaterCredit

Well, Gary White and Matt Damon, the authors of the worth of water book I just mentioned, also happen to be the founders of Water.org.

Since 2003, the organization has provided its own version of microcredit, called Watercredit. It distributed 9.6 million loans for an average of 360 dollars each and enabled it to change the lives of 43 million people.

And their repayment rate is simply astonishing: they’re reaching 99%. Simply put: it works!

Yet, is community involvement and microcredit sufficient if we want to end the water suffering of these 400 million sub-Saharan Africans and 785 million people worldwide?

Not yet. We’re missing fuel for that fire: we need more money.

Why “Credit” and not “Donation” like Water Charities usually do?

At that stage, you might wonder: why was Muhammad Yunus, and later Water.org, not giving that money to all the villagers and people we discuss here? Why lending it instead?

Well, for two reasons. We’ve already covered the first one: community involvement has proven the strength of people, being the heroes of their own journey.

If you take a loan, you also take the steering wheel!

Now, the second reason is financial.

Official Development Assistance (ODA) is at an all-time high

For the past 10 years in a row, the World has beaten its all-time high in development assistance grants, as an OECD note shows.

In 2021 it topped to $178.9 billion that got donated! But as amazing as it is, this money is by far not solely flowing to water projects.

First, regionally speaking, as we’ve widely discussed sub-Saharan Africa so far, these countries only attract about 18% of that ODA money.

… but only a fraction flows to Water projects

Then, even if globally mapping that money to specific topics is tricky, from what I deduct from the various OECD reports I’ve read, water projects would be categorized into the only section of development assistance that’s shrinking in 2021.

Finally, I can share with you this subjective feeling we got with Björn Otto when we prepared our live on World Water Day.

We contacted a dozen NGOs and Charities to ask them what they would do to solve the water crisis – and trust me, not the smallest there are.

It turned out that a vast majority simply answered that they don’t really deal with water. They do amazing environmental or climatic work; some also support refugees, but none of the ones that answered had structured water action plans. None.

I don’t mention that to name and shame – at all. I’d just like to underline there that the money won’t come from development grants.

Microcredit shifts the challenge

But remember, as we choose microcredit as our second tool, we also slightly shift the challenge. We don’t need that money to be donated anymore; it can be invested instead!

This means that we’re now tapping into a 1400 times larger pool: the global financial markets and their $250 trillion dollars.

Don’t take me wrong, there’s no free lunch either. Watercredit may well see a 99% payback of its loans, but it still doesn’t represent the juiciest investment you can make if you’d like your money to grow on the markets.

Water is not the sexiest stock there is

As Matt Damon and Gary White recall in their book, people gifted with a nice wealth usually whether invest their money to provide an excellent return on investment or donate it to charities.

So, convincing them that a path in the middle exists is a challenge.

We can actually map out that dilemma. On the first axis, we would have the social impact of our money. We would have the financial return we can expect from it on the second one. And in the middle of each of these axes, we would have a breakeven point.

This defines four zones in our graph:

- On the bottom left, we would have projects where we lose money and have a negative social impact. For instance, you would subsidize companies so that they extract more oil and worsen climate change. As if anyone would want to do that.

- On the top left, we have projects where we make good money but still have a negative social impact. You could think, for example of investing in tobacco companies

- On the bottom right, you have a positive social impact, but you’re losing money. That is the typical charity sphere.

- And on the top right, you have both a positive social impact and financial return: that sounds like the martingale, right?

The difference between Sustainable Investing and Impact Investing

If we further zoom in on that graph zone, we can still distinguish two approaches. You could focus first on financial return, which would typically be the case for sustainable investing and ESG funds. They pledge to a positive social impact, but they have to farm money for their investors.

Or, you could focus first on social impact while being just slightly above the fold. That would turn you into an impact investor, and that is actually the third tool we were looking for.

But how big of a tool is it? What’s the proportion of investors that are ready to earn only a little money for their buck?

The actual impact of impact investing

Out of the $250 trillion of Global Finance, the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance estimates that 15% flows to sustainable investing practices.

So, on our graph, the box on the top right, the martingale of positive financial and social impacts represents 15% of the total, for about $35 trillion as of 2020.

Of course, it still means that most investments are made with financial targets only, regardless of whether it is doing good. But the good news is that this section is growing year on year.

Tool 3: Impact Investing

Now on the zoomed-in view, the impact investing section, still according to GSIA, represents 1% of sustainable investing. Again, it doesn’t sound much, but it still means that $352 billion a year are invested by private actors with the first aim of doing good.

So imagine we manage to align the planets. We bring community involvement, microcredit, and impact investing together.

We have the engine, the tool, and the fuel to finally solve the water crisis.

Easier said than done, right?

Conclusion: the Future of Water Charities?

But there’s a full ecosystem at work. And if we all push in the right direction and join forces, we will succeed where states failed for decades.

Because there may well be a structural problem with states and NGOs. But I’m a firm believer; there’s no problem with the people inside. Let’s just give them the right tools!