OK, so we, the French people, maybe love Baguette, Red Wine, Frog Legs, we’re rude, we speak broken English and smell a little like our cheeses BUT we master the business of water (especially when it comes to mergers)! Right?

(I thought this example would be interesting, within my deep dive on Water Entrepreneurship)

Table of contents

Introducing VEOLIA & SUEZ

If you’re working in the Water Industry, it’s hard to miss the two largest water companies, Veolia and Suez.

I’m certainly not diving back into their story today because we extensively did that when covering their upcoming merger.

(and we even looked at it before the merger was sealed)

But talking of mergers, I’d like today to open the scary closet of both group’s top three failed acquisitions over the past two decades.

And that starts with number three…

Wait, not really. There’s one very important question we need to answer before:

Why would you go for a Merger?

For that, let’s be very rational. Even though this is thankfully a moving ground these days, the traditional definition of business is to increase the stockholder’s wealth.

There are actually two ways of doing so: Paying dividends and Increase stock prices.

Companies often try to combine both but to keep things simple today; I’ll consider them separate.

If you’re a mature business with limited growth opportunities, good cash flow, and low risk, the usual path is to go for dividends. A good example here may be the tobacco industry.

Now, if you’ve followed my latest episodes, you’d certainly not classify the water industry as having good cash flow and low risk, so I’d say, that’s not the easy track for us.

That leaves us with the option to trigger an increase in stock price.

How to trigger an increase in stock price?

Stock price evolution represents investors’ confidence in a company’s ability to make money in the future.

I’d say we can take a shortcut here: to increase stock price, the company must grow whether in revenue or profit, ideally both.

Option 1: Organic Growth

To grow, a company has two options again. First, it can expand organically. Your sales team gets new contracts, your product development launches new series, or you open new countries, regions, and territories.

The problem is, whenever the best brains, solutions, or business models, are no longer inside your company, you’re at risk.

And that growth path is rarely fast enough to content shareholders in a mature industry, such as the Water Sector.

Option 2: Mergers and Acquisition (M&A)

That leaves you with a shorter path to growth: mergers and Acquisitions, usually called M&A.

The Idea with M&A is to find other companies to buy on the market in order to increase your revenue and grow the mother company.

That can go in two dimensions – keep this in mind; it will be very useful for our Flop Three in a minute.

Two ways for a merger: Vertical or Horizontal

You can first go vertical. Vertical expansion takes you up or down across the value chain. If you’re a pump supplier, you can acquire a skid builder that used to integrate your pumps.

And if you’re an engineering company, you can buy a general contractor that usually transforms your designs into actual treatment plants.

Now, if that sounds pretty straightforward, it comes with a major risk.

Using your internal resources may not always be the best option, especially if more effective or less costly alternatives are available on the outside.

OK, but if you’re not going vertical, you can go horizontal. The Idea here, is to expand your company into its more or less direct adjacencies, with the hope to apply your skillset to this similar field.

This time, our pump supplier would buy a sensor manufacturer, and our process engineering company would go for a mechanical engineering one.

Special Kick to increase your merger’s chances: Adjacencies

Adjacencies can be this direct, or a bit more blurry if you estimate that even if the product range of your target is quite different from yours, you go through similar distribution channels or target the same customer base.

From a compatibility perspective, the safest of all adjacencies is to buy your direct competitor. Usually, he’s like your brother from another mother, so chances are that the skillset that brought you here still pertains true if you eat him up.

But neither M&A, in general, nor adjacencies, in particular, are a silver bullet. Sometimes (often?) the requested skillset to run the extended business wasn’t as similar as you’d expect.

And M&A also comes with a lot of drawbacks: it swallows your cash reserves, it loads your debt, and you have to issue more stock, diluting the value of each current share. Your key managers are overworked; others leave, culture clashes, morale can be shaky: in a nutshell, you’re lowering your productivity.

To round it off, because of the winners’ curse, which states that the winner of an auction always pays too much, a McKinsey study showed that target companies are usually bought at a price tag 10 to 35 percent above their real value.

The magical word that justifies almost every merger: Synergies

Considering all these negative aspects, why in the World would you still want to go for M&A?

Actually, because of a magical word: synergies.

Let’s look at some recent press releases announcing mergers in the water industry. If you want to play corporate bingo, tell me in the comments if you recognize which company wrote what!

“The acquisition will help ****** deliver on its ambition of offering a wider range of products and services to the wastewater network services sector, providing greater synergies to the shared customer base.”

“Solid synergies are expected from the pooling of complementary technologies, client portfolios and geographical presences.”

“There are also clear strategic synergies between ****** and ******’s business that we aim to take advantage of”

And so on, and so on.

Synergies exist, they are just less potent than prophetised

Let’s not paint everything in black here neither: yes, synergies exist. But not to the extent often prophetized.

In the same study I quoted just before, the McKinsey Group estimates that 70% of M&A fail to deliver the synergies promised at the time of the deal.

If you’re curious, check the full paper, you’ll read there how you shall account for “dis-synergies” such as the loss of customers and difficulties reconciling different service terms, or how one-time costs are often underestimated.

This preliminary work done, let’s move to our Merger’s Flop 3!

Failed Merger #3: Veolia and US Filter

In 1990, Dick Heckman bought what he described as “a crappy little company” called Toxxic Control for 1.6 million dollars. Changing its name to US Filter, he proceeded to transform it into a giant in less than a decade!

With the vision of building “The Coca Cola of Water,” he started acquiring other companies in an M&A frenzy that would bind hundreds of new pieces to the original US Filter. At the beginning of 1999, US Filter had become a clear US Water Market leader, with a revenue of 5.2 billion dollars and a profit of 276 million dollars.

The USA as a Green Field for Water Majors

At the time, the United States represented the World’s largest water market, yet still almost entirely controlled by a large number of small public-sector operators.

This was expected to change, with new laws that paved the way to greater private-sector involvement in water supply and treatment, both in the municipal and industrial worlds.

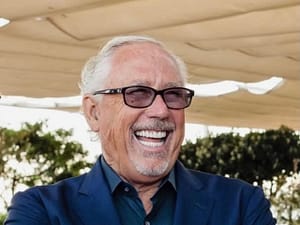

Veolia was then named Vivendi, and led by CEO Jean-Marie Messier.

I need to make a french reference here for you to understand who this key stakeholder in the story is.

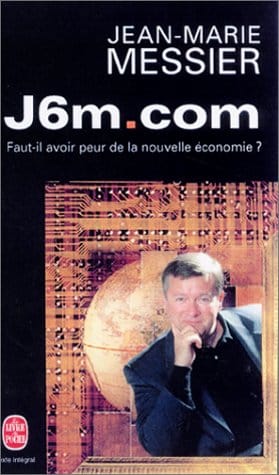

Introducing “J6M”

In France, Messier was nicknamed “J6M” standing for Jean Marie Messier Moi Même Maître du Monde” that I could translate into “Jean Marie Messier Me Myself Master of the World.”

The good side of his personality was that he had a never-ending ambition for Vivendi. And that was the bad side as well.

1999: Veolia acquires US Filter…

In March 1999, Vivendi closed the purchase of US Filter, for 6.2 billion dollars, with the ambition to pre-empt the US market, right before it would start to consolidate.

That move placed Vivendi back as the World’s largest water company, with an estimated 12 billion turnover and 67’000 employees.

Now the problem is, that on top of the 6.2 billion purchase, Vivendi was also taking over a 2.9 billion dollars debt, US Filter had built over its hundreds of previous acquisitions.

… and its Merger’s debt!

The year 2000 saw the initial public offering of Vivendi Environnement on the Paris Stock Exchange. But to reflect the difficulties of the US Filter subsidiary to deliver the expected results, the group had to depreciate its value by 2.2 billion dollars.

In 2001, again, Vivendi decreased US Filter’s internal valuation by 2.8 billion. And in 2003, Henri Proglio, that had taken over from Jean Marie Messier announced that they further depreciated US Filter, and were looking to sell it.

2004: Veolia sells US Filter to Siemens

2004 finally saw US Filter leaving the now called Veolia group, with the sale of 80% of the remaining assets to Siemens for 993 million dollars.

How do you turn a 9.1 billion investment into less than 1 billion in 4 years? Well, one answer may be that Vivendi bought at a high market hype, and Veolia sold on an all-time low.

But I’d say the root causes were a bit deeper.

What went wrong with that Merger?

To me, two factors were playing here. First, Vivendi was expanding vertically with US Filter, thus having the full end-to-end project scope under one roof.

As we’ve seen, this often makes sense in M&A projects but comes at the risk of losing competitiveness when you no longer challenge your internal solution with the market’s creativity.

And that was pretty badly received by the market, be it industrial or municipal, that had little confidence in Vivendi, under that configuration to deliver the best cost-performance ratio.

Around the same lines, you often had this tricky configuration where a Consultant or an EPC would be bidding against Vivendi for a large project but then have to work with its equipment division in later execution phases.

Culture eats Strategy for Breakfast

But maybe even more problematic, US Filter’s company culture was already between shaky and non-existent, given its Frankenstein nature, assembling hundreds of small pieces.

That clashed quite heavily with the behemoth culture of Vivendi, then Veolia.

It is interesting to note that Siemens, which then ran US Filter for a decade, did not do much better than Veolia, finally exiting for 872 million dollars in 2014 to AEA Investors, renaming the company Evoqua.

The best conclusion is to me the judgment Lukas Loeffler made, as the last CEO of US Filter before Siemens’ exit:

“Veolia did little to make it a company but continued to more or less run it as a conglomerate.”

Lukas Loeffler – Former CEO of Siemens Water (the former US Filter)

Culture eats strategy for Breakfast, apparently, Jean Marie Messier did not know the quote.

Failed Merger #2: SUEZ and Nalco

If there’s one universal truth to M&A, it’s that Mergers and Acquisitions breed M&A.

Remember what I just said: to raise your stock price, investors need to believe in your business perspectives and your growth.

So, if you’re happily growing at your organic pace, but all of a sudden, your biggest competitor goes mad and almost doubles its size through an acquisition, what do you do?

Well, you can stay calm and peacefully wait for it to turn into a disaster. Or you can go mad.

What? They bought something? I need to buy something too! Shut up and take my money!

If you’ve ever considered buying a new car just because your neighbor has a new car, you can’t blame that reaction.

SUEZ mimicks VEOLIA’s merger strategy

We’ve just seen that in the second quarter of 1999, Vivendi had acquired a large US water company and thus taken the water industry’s global lead, with a vertical integration strategy.

Well, in the third quarter of that same year, SUEZ decided to respond. They proceeded to acquire Nalco, a large US water company, with a vertical integration strategy.

The move on Nalco came right after a smaller one on Calgon, two weeks before. SUEZ’s ambition was hence to become the world leader on the industrial water treatment scene, with a particular emphasis on chemical treatments.

Founded in 1928, Nalco had almost reached 2 billion dollars in revenue by the time of the deal, drawing on steady organic growth over the past decade. Its customer base was 97% industrial and heavily concentrated in north-America.

1999: SUEZ acquires NALCO

To the market’s surprise, SUEZ bought Nalco for 4.1 billion dollars in an all-cash transaction, also taking over a 400 million dollars debt. The surprise came from the price, as the Nalco stock worth had rarely approached 40 dollars per share in that decade, whereas SUEZ was buying it for 53 dollars per share.

An analyst summarized the market’s thinking in one sentence:

“Nalco shareholders should be going out for martinis, celebrating the largesse of SUEZ Lyonnaise.”

Deutsche Bank Finance Analyst

But Gerard Mestrallet, then SUEZ’s chief executive, was confident he made a good deal too by bringing his company into the industrial market – thus a horizontal expansion – while now having end-to-end solutions in one pass – thus also a vertical integration.

SUEZ expected… Synergies from the Merger with Nalco

The company could proudly drop the magical word:

“We expect to realize more than $100 million in cost savings as a result of economies of scale, revenue enhancement, and development synergies, and to take full advantage of important cross-selling opportunities.”

And indeed, it was growing SUEZ’s water revenue by 32 percent while further expanding out of France and Belgium’s borders, with now 45 percent of the group sales abroad, half of which in the US.

SUEZ was running Mergers on high speed

The problem is that, in these very early 2000s, SUEZ – like Vivendi as we’ll see in a minute – was gobbling around and binding together a lot of quite unrelated companies.

Banking with Fortis, Insurance with AXA, Energy with Total, Civil Works with Vinci or even further TV Channels with M6 and Paris Premiere or Cable Operators with Noos, Coditel and Codenet.

But the general optimism around in 1999 had been replaced by 2002 by more gloomy times. The internet bubble had burst, and the belief that the sky only was the limit had vanished.

SUEZ was stuck in its debts, which topped at 28 billion dollars by the end of 2002. The sales of Northumbrian Water had helped a bit to improve the situation by 2003, and the group was actively looking to exit Total, Axa, Vinci, or Fortis. Yet, that was not sufficient.

Ondeo did not perform as expected

Meanwhile, the Ondeo business unit built upon Nalco, Calgon, and a part of Degremont did not deliver the expected profits. It was supposed to become the group’s rockstar. Instead, it was the black duck, delivering under average and piling up debt on debt.

Like Veolia had with US Filter, SUEZ realized that you couldn’t just plug a different culture in a wide melting pot and hope for the best.

So, in 2003, they decided it was time to cut Nalco out and started looking for a buyer. Its still strong North-American presence appealed to several US companies, of which, quite ironically, GE.

2003: SUEZ sells Nalco

But GE wouldn’t win: a consortium of Blackstone, Apollo Management, and Goldman Sachs acquired Nalco for 4.35 billion dollars.

Overall, it’s less of a bad investment than US Filter, so why is it higher in this flop list? Well, first because this is subjective, and I do what I want.

Then more seriously, for two reasons. First, it looks like SUEZ didn’t even try to integrate Nalco seriously. It was one of the many elements of an M&A frenzy, and when the time came to rationalize the group’s structure, it swiftly was characterized as non core.

Was SUEZ right too soon?

And that brings me to the real reason; this is a major flop to me. Just look at the market today: all the major water groups flourish in the industrial side of the market. To that extent, SUEZ was forward-looking with Nalco and the ONDEO business unit.

They just didn’t hang around long enough to reap the benefits of that strategy. And when you consider that the later acquisition of GE Water in 2017 brought them back in the exact place they left a decade before, especially with the Betz chemicals part that’s so close to Nalco, it makes you wonder what would have happened if they had stayed with the original vision.

It’s hard to be right too soon!

Merger Fail #1: Vivendi and Universal

I’ll be much shorter – or at least I’ll try – for our number one because you’ll swiftly notice how it goes far beyond the Water Industry.

Take an ingredient of the US Filter story: “J6M” or Jean-Marie Messier, Me, Myself, Master of the World, the then CEO of Vivendi. And take an ingredient of the Nalco story: being right too soon.

Blend them, and you get one of the largest economic failures of all time.

M&A and Diversification was built in the Compagnie Generale des Eaux’s roots

But let’s go back a bit in time first. Founded in 1853, the Compagnie Générale des Eaux that would one day become Veolia had a history of success and diversification.

Already in 1864, its stock exchange success resulted in the creation of the “Societe Generale,” still one of the largest French banks, over 150 years later.

In 1998, the Compagnie Generale des Eaux changed name to become Vivendi, and better reflect its ambition to grow beyond water.

The sturdy, profitable business of water would serve as the cash cow to more adventurous investments, exactly like when, in 1996, 4.2 billion dollars of water provisions had been used to pay off some of the group’s other branches’ debt.

Mergers far beyond the scope of Water

We’ve seen that Vivendi’s first large M&A move of 1999 was in its core business, with US Filter. But that same year, Vivendi also acquired the TV Channel Canal+, France’s second-largest telecom operator, SFR, and the Cinema studio Pathé.

Now, the largest move was still to come. In June 2000, Jean Marie Messier announced the acquisition of Seagram for 40 billion dollars plus 7.6 billion of debt.

You may not know Seagram, but you probably know the shiniest company that was inside: Universal. You heard it right: from the Rolling Stones to Justin Bieber – ok, not by then for Justin, as he was only 6 – all the biggest musical names now belonged to a french water group.

That came with Studios in Hollywood and participations in several US television networks.

An M&A Frenzy that deepens the Debt

From then on, Vivendi acquires an average of one company per month. Maroc Telecom, Uproar, Houghton Mifflin, emusic.com, HCCom, Scoot Europe, RMM records, MP3.com, Elektrim, Echostar, and finally USA Networks, for a total of 23 billion dollars in one year.

But the debt becomes abyssal. The Vivendi share loses 70% of its value in one year. The company runs out of cash, and loses 13.6 billion dollars in its first year. Banks don’t want to play along anymore.

From New York, where he now lives, Jean Marie Messier takes his nickname of Me Myself Master of the World a bit too seriously. He gets raving applauses at the World Economic Forum, but a revolution is cooking in the corridors.

In July 2002, Messier is asked to leave. The group is slowly dismantled piece by piece, while the core environmental activities get extracted with the IPO of Vivendi Environnement, eventually becoming Veolia.

Was Jean-Marie Messier right too soon?

Almost 20 years later, if we look back, that Vivendi Universal group had the telecom, the media content, and the diffusion channels. It was tailored to succeed 15 years later. But as we’ve seen, you can’t be right too soon.

And who knows, in an alternative timeline, Netflix or YouTube may have been french and broadcast hours of water-related content.

See you soon!