The largest British Water Company is steps away from Bankruptcy, and that’s just the latest news in an incredible downward spiral: let’s review!

with 🎙️ Antoine Walter, Podcaster in Chief at GF Piping Systems

Is Thames Water on the Verge of Bankruptcy?

Table of contents

- Is Thames Water on the Verge of Bankruptcy?

- Thames Water is UK’s largest Water Company

- The origins of UK’s Water Companies

- Thames Water’s take over by RWE didn’t go as well as expected

- Water Utilities are a CAPEX intensive business

- Thames Water suffered a repeating pattern of underinvestment

- The questionable dividends of UK Water Companies

- What happens now for Thames Water?

- What’s the bigger picture for UK Water?

- Other Episodes:

Thames Water is UK’s largest Water Company

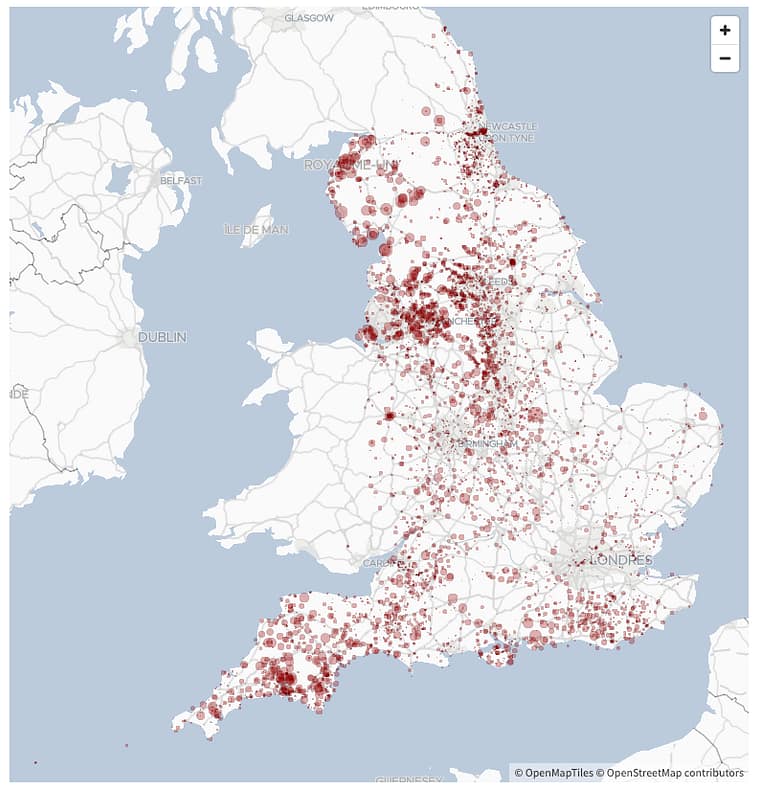

Thames Water serves 15 million people across London and the Thames Valley with water and wastewater services – now the question is, does it serve them well.

Well, the water services regulation authority answered with a kind of bold “no” last year when it imposed Thames Water a 51 million pound penalty for a combination of missed targets and pollution incidents.

In 2022, Thames Water’s wastewater networks were spilling untreated sewage to the environment for a little less than 75’000 hours, which, if it doesn’t make it UK’s worst pupil, isn’t necessarily something to pride itself on either.

Thames Water’s kept failing to achieve its quality KPIs

At the same time, the company’s water networks are estimated to lose the equivalent of 250 Olympic swimming pools worth of drinking water every day – or the equivalent of 10’500’000 wheelbarrows. Because why would we have to measure everything in swimming pools?

Water supply interruptions nearly doubled between 2021 and 2022, the water quality compliance risk index was multiplied by 6, and as alluded to with my wheelbarrows, leakage rose again by 3%.

Thames turned in a record loss in 2022 coupled with a concerning £14 Bn debt

But the main reason why the company is in trouble is to be found in its financials. The company reported a nearly 1 billion pound loss after tax in its last annual results while dealing with a debt that reached 14 billion pounds, of which about half of it is linked to the inflation rate – which adds to the pressure on Thames Water’s throat in inflation times.

Last but not least, the company has been left without its CEO since last Wednesday as Sarah Bentley resigned.

A couple months ago, she told BBC about her tenure as Thames Water’s CEO:

Indeed, to understand the situation Thames Water is in today, we have to swiftly look at what a water business actually is in the UK.

The origins of UK’s Water Companies

Since 1989, water and wastewater utilities have been privatized, but unlike transportation or energy, they’re locally monopolistic. If you live in London, you get your water from Thames Water, and they’ll also deal with your sewage.

So, on the surface of things, it’s a license to print money: you get good quality water from the environment, you lightly treat it to drinking water standard, let it flow through your network that’s amortized for a while, given the largest investments date back to victorian times, people have to take it and pay for it as you have no competition, they flush it when done, water flows further through your victorian network, you treat it to preserve your resource, and you rinse and repeat.

A supposedly simple investment strategy

Easy cash, steady income with a cherry on the cake: in 1989 the water companies got privatized debt free and with a little bit of cash on hand to deal with daily expenses.

Now to be fair, the water companies also got privatized because the British government didn’t want to cope himself with the upgrade of wastewater treatment. So there was kind of a body in the trunk, but that’s a different story.

Thames Water’s take over by RWE didn’t go as well as expected

In the year 2000, a German company, RWE, got a bit too inspired by the French Vivendi – you know, the one we covered in my flop 3 of Suez and Veolia’s worst mergers.

By acquiring Thames Water, RWE became the third largest water company in the World, and they would proceed further down that path by adding American Water to the pot in 2003.

That story in itself would be worth a deeper dive, but for today, let’s stick to: it didn’t perform as expected, and RWE retreated from water by selling Thames Water in 2006 to a consortium, Kemble Water, led by Australian bank Macquarie. They would then proceed to spin off American Water as well, through an IPO.

Thames Water’s overtake by Macquarie piled up a bunch of debt

By the time RWE let Thames Water go, the company had accumulated 3.2 billion pounds of debt.

It wouldn’t get better under Macquarie’s lead, which would last until 2017, a point at which the company’s debt had reached 10 billion pounds. And as I mentioned, that debt would then keep increasing until today’s 14 billion.

But why so much debt? Why would a “license to print money” business drag a balance sheet so much in the red?

Well, actually, because running a water utility business is a very difficult equation where you always have to re-invest in your asset if you want it to not start bleeding more money.

Water Utilities are a CAPEX intensive business

Any point of the water cycle where you start under-delivering is a potential snowball effect. Let’s imagine you let untreated sewage spill into the environment. Like that would ever happen, right?

As a consequence, your water source gets less pure and wholesome, and on top of the environmental damage, you need to beef up your water treatment, which is an additional cost.

Same story with network leaks: that’s more water you need to produce to keep serving your users while managing the consequences of millions of wheelbarrows of water flooding your city’s underground.

Now if there’s something that every of the successive runners of Thames Water agrees on, it’s that the company’s asset are in, let’s say, a challenging shape.

Thames Water suffered a repeating pattern of underinvestment

Sarah Bentley, again:

A “broken company” that’s been “hollowed out” that’s strong words by Sarah Bentley. And indeed, Thames Water recently committed 1.6 billion pounds to the reduction of sewage spillage.

But that’s nothing so new either, as Macquarie’s last press release to announce the final sale of their Thames Water shares also highlighted how under their governance, they spent 1 billion pounds a year on network maintenance and expansion.

That was allegedly 72% more than what had been done between privatization and their takeover in 2006.

So modern Thames Water invests more in its assets than Macquarie’s Thames Water, which itself invested more than RWE’s Thames Water… which itself invested more than public Thames Water at least in the 5 years prior to privatization.

Was Thames Water running bad investments?

Well, one could think so right? You’re pouring money into a pot that leaks faster than you pour. Yet, still to this date, pension funds haven’t reduced their interest in Thames Water. Today’s owners of the company include the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, the Universities Superannuation Scheme, China Investment Corporation or British Columbia Investment Management Corporation.

So what is it that they see and that we miss in that picture?

To understand this one, we need to zoom out and look at the entire British water scene.

The questionable dividends of UK Water Companies

Remember, in 1989 Margaret Thatcher initiated the water sector’s privatization, which got effective in 1991, with zero debt across the board.

By 2019, though, the entire water sector had accumulated a 48 billion pounds debt. But here’s the catch: it also paid off 57 billion pounds to its shareholders over this same period. To round off the picture, 123 billion pounds got invested in infrastructure projects, which were covered by customer bills.

To take a shortcut: the debt has allowed paying dividends, while water otherwise somewhat pays for water.

That’s quite an unhealthy situation, right? And even though Thames Water is under the spot, given its debt dangerously nears its legal maximum, it’s not the only company at risk. Ofwat said last year that it was concerned about the financial resilience of Yorkshire Water, SES Water, Southern Water, and Portsmouth Water, as well as Thames Water.

What happens now for Thames Water?

Well, first, Thames Water is in a bad position, but not a desperate one. With 4.4 billion pounds of financial liquidity, they’re supposed to have enough cash on their hands to stay in business at least until March 2025.

In between, it’s going to be a race against the clock. Indeed, as Sarah Bentley told BBC:

The only thing that’s changed since that interview is that the race will now happen without her.

What’s the bigger picture for UK Water?

In the bigger picture, the Thames Water situation is one of these mirrors where you can see whatever you’d deeply wish to see.

Some will see it as proof water shall be managed in a public manner, as a private company is kind of failing. Others will rather see it as evidence it’s a private tiger without teeth, as there’s no competition in this local monopoly scheme. And I would probably tell you that networks are a damn sunk cost at which we should try to reduce our exposure by rapidly developing a decentralized and distributed approach.

But the truth, everyone would probably agree upon, is that we’ve underinvested in water for too long and that now it shows. Wanna fix that? Have a look here, and I’ll see you next time!