In 2034, the World will spend more on bottled water than it does on utility water. Five hundred ninety-eight billion dollars a year spent in Evian, Aquafina, or Dasani. That’s more than the GDP of a country like Belgium, but what does that tell us?

(maybe, that tells us that you shall look at my full deep dive on water networks!)

Table of contents

- The origin of Bottled Water

- How Perrier revolutionized the Bottled Water market

- Perrier created a new market Category for Water in Bottles

- High-End Water in Bottles: a Second Veblen Good

- Why will bottled water out-finance utility water by 2034?

- Could “Point of Use” treatments be the best of two worlds?

- What would be the cost of Point of Use treatment?

- Point of Use Vs. Bottled Water

- Conclusion

The origin of Bottled Water

The Holy Well Bottling Plant in the United Kingdom is considered to be the first bottling water plant in the World. In 1622, they started filling glass bottles with their mineral water and selling it.

The marketing promise behind this move was to offer the medicinal value of that mineral water to people that had no access to the source. That medical claim was the main selling point of water bottles that pharmacies mainly distributed until the early twentieth century.

Today’s point is not into the full details of the bottling history, so I won’t tell you too much about how Johan Jacob Schweppe discovered how to carbonate water in 1783, or how Dupont patented Polyethylene terephthalate in 1973, thus opening the market to PET bottles.

Bottled Water could have disappeared in the early 1900s

Indeed, bottled water could have died long before the age of PET. Tap Water became much safer at the beginning of the twentieth century when disinfection methods became popular, notably ozone and chlorine.

And indeed, until the 1970s, bottled water was much of a niche. At the beginning of that decade, only 1 billion liters a year of bottled water were sold in the USA, a good chunk of it being the 5-gallon bottles you could find in the offices.

But a revolution was cooking, and as often with revolutions, it came from France.

How Perrier revolutionized the Bottled Water market

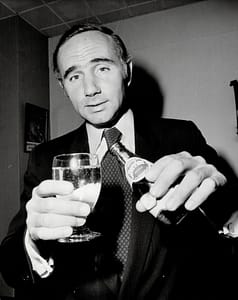

In the late 70s, Perrier was a sparkling water brand, essentially distributed in high-end restaurants. But they ambitioned to become much more and to reach the mass market in the USA.

So, they hired Bruce Nevins and initiated a market blitz with a wealth of TV ads, voiced by no less than Orson Welles. Some were pretty classic.

Some were quite… let’s say edgy.

All the specialists were predicting a major failure. “It’s like selling canned air; why would people spend a fortune to buy what they can get for a fraction at the tap!”

Selling a Lifestyle rather than Water in Bottles

Well, that’s where everybody was wrong. Perrier wasn’t really in the business of selling water. They were selling a lifestyle.

Baby boomers had a strong desire for status? Perrier was bringing it in a rounded green bottle. And the taste of France, Terroir, and Fame, with all the stars and sports players posing next to it, was swiftly making it a Veblen Goods.

Bottled Water as a Veblen Good

Let me pause our story here to explain what a Veblen Good actually is. And it’s pretty important because what happened in the seventies is currently happening again, so please bear with me.

You’ve probably heard a million times that price is a result of demand. If many people want a good, the price tag increases, as the offer may struggle to follow demand.

Well, a Veblen good is quite the opposite. People get attracted by a high price tag, as it is an easy way to distinguish themselves from the masses that cannot afford such a conspicuous consumption – to use the term coined by Thorstein Veblen in 1899.

Sometimes also called the “snob effect,” that cognitive bias is the one that enables Balenciaga to sell a white t-shirt 100 times its real value by just applying its logo on it.

In a nutshell, it’s all about stuff that’s expensive and hence has to be superior.

Perrier created a new market Category for Water in Bottles

That’s how Nevin actually created a category, positioning “pure Perrier” as the perfect mixer for the fanciest cocktails, as the healthiest partner for your sports activities, or simply as your piece of France in a bottle, that made you special.

And experts predicting a failure were somehow right. It did not work. It SKY-ROCKETED!

In 1980, Perrier had multiplied its sales by 70, then proceeded to acquire its main US competitor, and reached 85% share of a booming market.

But wait, I see the doubt on your face. You still don’t believe that it’s all about marketing, right? We’re rational human beings, after all. And if you ever tasted Perrier, you and I know that it’s simply better than tap water.

Bottled Water is not Better or Safer

Well, in 1986, Bruce Nevins, that had become Perrier’s North American CEO was trapped into a blind test by KABC radio, where his own sparkling water was hidden among a dozen of other brands. And guess what, he did not recognize his product and very honestly admitted that the value was in the brand, not in the carbonated H2O inside the bottle.

So what’s left if it’s not better? Is it safer? Well, in the 90s, a small number of Perrier bottles were found to contain benzene. Ouch. Sure, sales plummeted, but not to the benefit of tap water, rather as transfer to Evian, or the new brands created by Coca Cola and Pepsi.

Today in California, 80% of people only drink bottled water, and in a country of iconic soda brands, bottled water surpassed carbonated drinks as the number one beverage in 2017.

High-End Water in Bottles: a Second Veblen Good

But there comes our second Veblen Good. Because, if bottled water now becomes a commodity, and you’re still a hipster, wanting to distinguish yourself from the masses. How do you deal with that?

You could return to tap water as your grandparents did. Sure, it’s vintage.

Or, you could open a brand new market segment. And guess what happened…

Today, you can drink “Iceberg Water” – which is guaranteed to come from a melted iceberg, thank you global warming.

Or you can go for BLK Water, a water which is actually black, thanks to its high fulvic mineral content.

Sometimes it’s even more straightforward, with, for instance, Bling Water.

I think you got my point, so let’s zoom out. Are all consumers of bottled water victims of marketing? Well, sadly, No.

Why will bottled water out-finance utility water by 2034?

Remember my introduction? The investments in bottled water may take over utility water in 2034, but today, apart from Mexico and a close call in the US, utility is still ahead.

And if the World is on a track to raise its bottled investments from one hundred twenty-three Billion dollars in 2015 to $429 billion in 2030, it is widely because utilities will fail to close the water gap themselves by then.

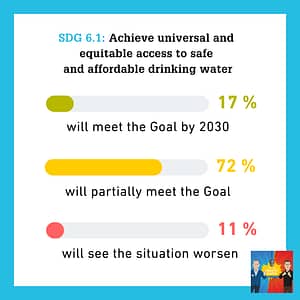

Failing to achieve SDG6

If you remember the UN Sustainable Development Goal n°6 we already touched on, it boils down to enabling universal access to water and sanitation.

Let’s face it, we’re far from achieving this target, even on the water side. Utilities don’t get sufficient funding today in most places around the World to sustain their existing assets. This, in turn, means that they’re far from investing in the additional capacity that may bring drinking water to every household.

And I’m not even addressing intermittent service, water scarcity, or non-revenue water here – we would have to make a specific deep dive for that.

(and Spoiler, we will!)

Bottled Water is a Good Alternative when there’s no other one

Now it’s hard to live without water. So bottled water is a safe and convenient alternative if you can’t find water anywhere else.

Safe. Convenient. But expensive. When you spend 500 billion on bottled water, you don’t get the same amount of water that when you spend 500 billion on utility infrastructure.

Yet, I’m honestly not sure either that pushing everywhere the traditional central utility approach would be a much better solution than getting all our drinking water in bottles.

Large infrastructure comes with its own caveats ranging from inefficiencies and high operating costs to heavy capital needs through diverging incentives and even corruption.

But does it really have to be this blue pill / red pill alternative? Well again, no!

Moving out of the Tap Vs. Bottled Water debate

I’m not sure it’s a positive thing for the World to let bottling companies and Utilities fight in a lose-lose war where utilities only underline how cheaper they are…

… while bottling companies create ads that degrade people’s trust in their tap water.

There are, in fact, dozens of other avenues to explore. So, it’s maybe time to be creative!

Let’s pick only one for today, and let’s take the World’s number 3 as we speak: Point of Use treatment.

Could “Point of Use” treatments be the best of two worlds?

Indeed, Point of Use has a bit of the beauty of the “in-between.” The principle is to treat water, as the name states, at its point of use.

In the developed World, it often takes the shape of an under-the-sink unit, while in the developing World we see two types of systems, table-top gravity-fed filters (remember my conversation with Sreenath Bolisetty from BluAct) or small RO-UV devices.

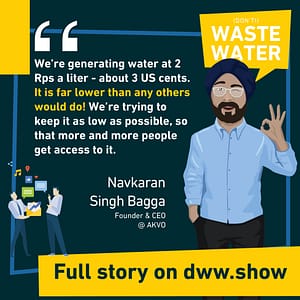

We could also factor in here atmospheric water generation – have a look at my discussion with Navkaran Singh Bagga from Akvo to that extent!

When operated and maintained the right way, all these units will deliver satisfactory drinking water quality. So, you can forget about the trust issue in utility water, while avoiding the hassle of collecting and disposing of bottles.

If you even want to reproduce the taste of your favorite mineral water, that’s possible – check my discussion with Jacob Bossaer from Bosaq!

What would be the cost of Point of Use treatment?

But what about the costs?

A typical “developed world” system costs 200 to 500 dollars for the unit along with a 60-80 dollars annual running cost. Assuming a replacement every five years, the total yearly cost is thus 130 to 180 dollars.

Let’s compare it to bottled water now. In a bulk pack and in the western World, it costs 0.35-0.50 dollars per liter (not accounting for the time needed to do your groceries, the gasoline, and the maintenance of your car, and assuming you don’t go for iceberg water).

That brings our cost per capita for bottled water to about 450 dollars and the annual cost for an average 2.5 people household to 1125 dollars.

So, we can estimate that Point of Use water is seven times cheaper than bottled water in developed countries.

And in developing economies?

But how about the developing economy. Gravity-Fed table-top units cost about 19-43 dollars, plus 5-10 dollars per year to replace the cartridges. Assuming a three-year lifetime for your unit, the total annual cost is 11-25 dollars.

Then, you could also go for RO + UV units, which cost 75 to 190 dollars, with an annual running cost of 15 to 50 dollars. With a five-year lifetime, that makes a total yearly cost of 30 to 90 dollars.

In a 20-liter jar, basic bottled water costs about 90 rupee, which makes for 6 dollar cents per liter. We thus get an annual cost of 77 dollars and an annual charge for the average 4.5 people household of 353 dollars.

Point of Use Vs. Bottled Water

Now “Point of Use” does not need to be designed for single households neither. We could imagine winning additional scale-effect and cross efficiencies at the district level. That would turn “Point of Use” into decentralized treatments and micro-utilities.

Kind of a 21st-century re-interpretation of the utility, leveraging the power of digitization while skipping the part where you have to lay hundreds of kilometers of enormous pipes.

But that’s a different story we will cover another time!

Conclusion

Now, if there’s something that the aspiring solution shall copy from the bottled water industry, it’s for sure its marketing.

Here’s a suggestion. Micro-breweries are booming, right? So what if the next identity move for hipsters of all kinds was to support the development of their local micro-utility?

And if you have a better marketing Idea of how to promote tap or point of use water, come tell me in the comments.

See you soon!