Had the people of this top 5 not existed, who knows how our water would look like… Here’s why I’d qualify them as most influential for the Water Industry!

Can you guess who they are from the get-go? Here’s a hint: I have a simplified version of one of their inventions in my garden (next to my pond). Did you guess which one? No worries, we’ll see that in a minute.

This is a section of my deep dive on Water and Wastewater Treatment.

Table of contents

- Most Influential People #5: The Man who Defied a US President

- Most Influential People #4 : The Water Detective that Triggered an Industry Revolution

- Most Influential People #3: The Man that Triggered Desalination – and got a Dismal Reward

- Most Influential People #2: The Guy that made Drinking Water “Pure and Wholesome”

- BONUS: Harriette Chick

- They could have made to the top of my list of Most Influential People in the Water Industry…

- Most Influential People #1: The technology, that’s somehow in my garden

- The most influential people in the Water Industry: CONCLUSION

Most Influential People #5: The Man who Defied a US President

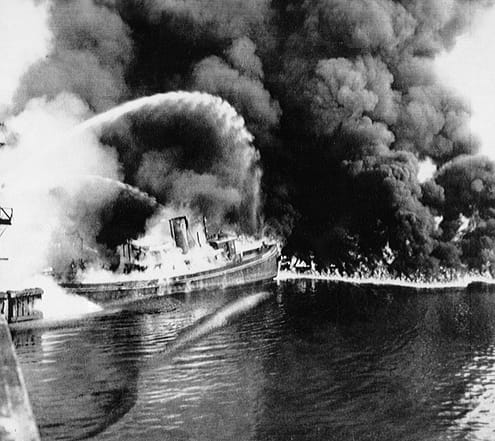

Have you ever seen a river catch fire? Not a boat on the river, the actual river.

Well, in the 1950s and 60s, this was quite common in the united states. Industries, sewers, and neighbors were dumping massive amounts of garbage and chemicals into rivers and lakes. And that ignited several fires, on, for instance, the Buffalo River in New York or the Rouge River in Michigan.

Yet one river was the all categories’ champion when it came to fires: the Cuyahoga in Cleveland.

In 1969, it took fire for what’s considered to be the twelfth and last time. It wasn’t the worst of all fires in terms of damage, but it got Cleveland some really bad press, with notably a Time magazine article explaining how the river oozed more than flowed.

As a more or less direct consequence, Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin founded Earth Day. Meanwhile the US Congress passed the National Environmental Protection Act in 1970, which would establish the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

Yet all of this was still only partially addressing the problem. Without any real regulation, wastewater was barely treated in the US beyond basic mechanical screening.

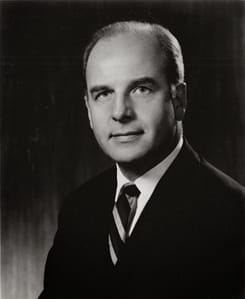

Introducing: Edmund Muskie

Edmond Muskie was a lawyer by education. He had started his political career upon returning from the second world war, and had been a member of the Maine House of Representatives. Then becoming the 64th Governor of Maine in 1955.

In 1959, he was elected Senator from Maine, and would sit in the US Senate until 1980. In the 1960s, he had been supporting the environmental movement, advocating for increased water-related regulations, and contributing to the Clean Air Act.

But in 1971, he was about to go a huge step further.

He indeed introduced a bill in the Senate to amend a 1948 law.

In his speech to his colleagues, Muskie went lyric: “This country once was famous for its rivers. But today, the rivers of this country serve as little more than sewers to the seas!”

Senators indeed recognized he had a point; the Bill got accepted by eighty-six to zero.

Towards the “Clean Water Act”

But that was only the beginning of the route. The Bill traveled to the Public Works Subcommittee on Flood Control and Internal Development before getting discussed at the House of Representatives in March 1972. The reps added four amendments but validated the Bill by 380 to 14.

It then took 40 meetings between the two chambers to reconcile both versions of the text. Many predicted the Bill would die in conference, as things were starting to really drag on.

But Edmond Muskie’s determination was flawless. He was active both on and behind the scenes.

On October 4 1972, both houses adopted the conference report. The House of Representatives passed the legislation by 366 to 11. Then, the Senate also adopted the latest version of the text by 74 to 0.

The Bill was thus sent to president Nixon on October 5, 1972.

From then on, Nixon had ten full days (excluding Sundays) to sign the Bill or it would simply be deemed adopted. So that left him until October 18 to react.

But on the 17th, shortly before midnight, Nixon decided to… veto the text.

His motivation was, that the legislation, which would later be known as the clean water act, would effectively continue the efforts to raise water quality, but at the expense of extreme and needless overspending. To him, that was not serving the public interest.

Because who cares about rivers right?

Overcoming Nixon’s Veto

In thus cases, both House of Representatives and Senate must proceed to a new vote. A two-thirds majority is required to overrule the presidential veto.

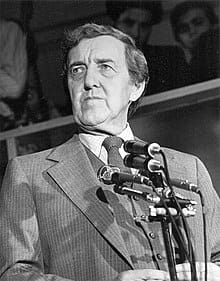

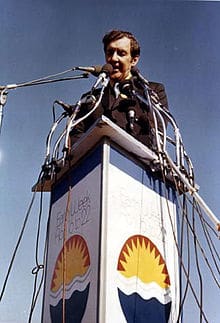

A last time, Edmond Muskie climbed the steps to the podium. He knew, this was the decisive battle. “Can we afford clean Water? Can we afford rivers and lakes and streams and oceans which continue to make possible life on this planet?”

His colleagues answered with a big yes. 247 to 23 at the House, 52-12 at the Senate. The president was overruled, and the Clean Water Act was enforced.

Edmond Muskie’s determination had paid, secondary treatments were rolled out in the country’s wastewater treatment plants, thus gaining them the right to be REALLY called treatment plants!

Most Influential People #4 : The Water Detective that Triggered an Industry Revolution

April 5, 1993, Milwaukee. The laboratory’s Chief Virologist’s phone starts ringing. People report apparent gastrointestinal diseases. And that first call is only the beginning of a massive wave.

Within the next hours, pharmacies report that they are sold out on anti-diarrheal medication. Hospital laboratories call each other in panic and confirm their suspicions: it’s happening everywhere in the city.

When such a large population suffers the same disease at the same time, eyes usually turn to the Water. The health department proceeds to call Milwaukee’s two water treatment plants to get their water quality data.

But to their surprise, the only sign of something happening is a slight increase in turbidity. But still within federal limits!

Two days pass, and a full city is suffering from intense diarrhea. Meanwhile, no one can put a name on what’s happening. Finally, by day three, the culprit is identified. It’s Cryptosporidium.

The parasite had indeed infected the Howard Avenue Water Treatment Plant.

Over the total outbreak, 400’000 residents had been affected, and 69 people lost their life.

Introducing: Joan Rose

Professor Joan Rose was called onsite and appointed principal investigator.

In her late thirties at the time, Joan Rose had already run the investigations in Carroll County when it suffered a Cryptosporidiosis outbreak in 1987. And she was rapidly becoming one of the World’s references on water microbiology, water quality, and public health safety.

Together with her team, which she calls “water detectives,” she developed new genetic analytics to study waterborne health threats.

Over her career, she investigated numerous waterborne outbreaks worldwide, such as the Milwaukee event we discussed seconds ago.

She studied Water used for food production, drinking water treatment, wastewater treatment, and reclaimed Water.

Overcoming Cryptosporidium – and creating the Membrane Market

Restricting Joan Rose’s influence to cryptosporidium would be quite of a shortcut. Yet, that field alone had tremendous consequences.

In the 1990s, most of the countries adopted regulations to eliminate crypto and the like in drinking water plants.

But those parasites are extremely resistant to disinfection and quite small in size. This limits the number of treatment technologies that can address them.

If you’ve listened to my interview with Graeme Pierce, you already know it, but that had a major consequence: it created a market for membrane treatment, arguably the largest revolution in Water over the past 30 years, with ultrafiltration membranes becoming a go-to in drinking water production.

Professor Joan Rose keeps advancing her field of science ever since, receiving on the way some of the most prestigious awards and recognitions in the water world, like the Clarke Prize, Singapore’s honorary citizenship, and the unofficial “Water Nobel” aka the Stockholm Water Prize in 2016.

Dear Joan, whenever you read this, consider it an invitation; I’d be incredibly honored to have you on my podcast microphone!

Most Influential People #3: The Man that Triggered Desalination – and got a Dismal Reward

In 1748, Jean-Antoine Nollet, a french physicist, ran some experiments on a pig’s bladder and discovered the process of osmosis. Indeed, the solvent could selectively pass through the bladder membrane!

For two centuries, that did not seem to raise much interest. But in the aftermath of the second world war, water scarcity became a topic of increasing strategic interest.

In the 1950s, a young Massachusetts State Senator regularly expressed his belief that large-scale desalination shall probably be an accurate answer to this rising concern.

So when that Senator became president in 1960 – do you know John Kennedy? – the desalination topic got an additional kick that triggered larger-scale research.

The University of California took the lead, and started developing a membrane. Several designs were studied. The winning one came from a project led by Sidney Loeb, in partnership with Srinivasa Sourirajan.

Introducing: Sidney Loeb

Their concept was an asymmetric Reverse Osmosis membrane built out of cellulose acetate. It selectively rejected sodium chloride and total dissolved solids under pressure while allowing Water to pass through.

Which, when you think of it, is exactly what you expect from a successful desalination membrane!

Loeb continued the membrane’s development, together with his professor at UCLA, Joseph McCutchan, resulting in even higher salt rejection, and increased strength.

In 1965, it was time for the concept to leave the laboratory, to be tested out in the real World.

The team found a perfect application case with a small Californian town, Coalinga. Its Water had become unpotable due to a high presence of minerals.

On June 4, 1965, Coalinga kicked off the pilot. It would last three and a half years and prove a point: yes, reverse osmosis membranes were a great answer to President Kennedy’s request for large-scale desalination.

But surprisingly, Kennedy never visited the plant…

Establishing Desalination

Many additional desalination plants installed reverse osmosis systems in the 1960s and 70s, while the technology got adopted in the industrial World. But cellulose acetate also showed its limits: it doesn’t allow high pH, limits the temperature of operations, and requires around 30 bar of pressure.

Hence, new RO membrane designs were developed, like John Cadotte’s one, using polyamide, in 1972.

Today, Reverse Osmosis is estimated to be a 3.6 billion dollar yearly market. And that all can be traced back to Sidney Loeb’s original patent, filed in 1962 and issued in 1964.

Yet, for all the duration of that patent, Loeb only received fourteen thousand dollars.

It’s hard to be an influential water scientist and a successful businessman at the same time…

Most Influential People #2: The Guy that made Drinking Water “Pure and Wholesome”

In 1899, Jersey City had a problem. Their drinking water supply was heavily polluted with sewage so that they decided to… create a new drinking water supply.

I know, nowadays, we would probably rather treat the wastewater, but things were quite different at the turn of the twentieth century.

The project involved a new dam on the Rockaway River to build the Boonton Reservoir, of which Water was drawn and directly piped to Jersey City, without any kind of treatment.

The Jersey City Water Supply Company that was running the project had by contract to deliver “pure and wholesome” Water to Jersey City.

I would love to bring such a clause to a legal department nowadays, to see their faces become green, purple, or red.

The problem is that the Water turned out to be less pure and wholesome than expected. Sewage was entering the river upstream of the reservoir and kept contaminating it. So the city filed a lawsuit against the Water Supply Company.

In 1908, the Chancery Court of New Jersey concluded that indeed, two to three times per year, the Supply Company wasn’t living up to its “pure and wholesome” promise.

Hence, they were given three months to whether pay for the construction of sewers in the Rockaway River watershed or come up with “other plans or devices” that would enhance the drinking water’s purity.

Introducing: John Leal

John Leal was employed at the time by the Jersey City Water Supply Company as its sanitary adviser. And he estimated the sewer construction option to be quite unrealistic, which led him to look for alternatives.

He, in fact, had been testing for ten years the application of chlorine on Water in his laboratory. The idea stemmed from two previous experiments, the first in Maidstone, England, after a typhoid fever outbreak n 1897, and the second in Lincoln, England as well, after a similar event in 1905.

John Leal‘s intuition was that there was a way to enhance those first approaches by using chloride of lime instead of sodium hypochlorite, and he hired George Fuller to do exactly so.

Honestly, George Fuller could also have made it to my top five list, as he had already in 1908 a strong track record of influential achievements in the water industry, such as the addition of aluminum sulfate to enhance mechanical filtration.

Establishing Chlorination

Fuller, the sanitary engineer, and Leal, the physician, had not only to invent quite everything around that plant. They also had to hold an impossible deadline. Remember, the court had given the Water Supply Company three months to come with “other plans or devices.”

Quite a challenge, but the two men did it: 99 days later, the chlorination facility fed 0.2 to 0.35 ppm of chlorine to an average water flow of 40 million gallons a day coming from the Boonton Reservoir.

When the case went back to court, the judge was convinced.

I do therefore find and report that this device is capable of rendering the Water delivered to Jersey City, pure and wholesome, for the purposes for which it is intended, and is effective in removing from the Water those dangerous germs which were deemed by the decree to possibly exist therein at certain times.

The consequences would go far beyond just Jersey City. By 1914, 21 million people received chlorinated Water in the US, and by 1918, one thousand North American cities had implemented it. As a consequence, typhoid fever death rate in the US tumbled.

Jersey City still chlorinates its Water, which makes it the second oldest disinfection plant in operation, after Nice in France, and its ozone treatment plant.

BONUS: Harriette Chick

There’s a third pioneer I could have associated here with Fuller and Leal, that’s Harriette Chick. Indeed, the British microbiologist formulated her famous Chick’s Law the same year the Jersey City plant went into operation, in 1908.

That chemical Law, slightly amended by Herbert Watson into the Chick-Watson Equation, gives the relationship between the killing efficiency of organisms and the contact time with a disinfectant.

And it’s still used today to design the plants that build for the 8 billion dollars annual disinfection market.

They could have made to the top of my list of Most Influential People in the Water Industry…

Before moving to number one, I have to tell you that this list is, of course, very subjective.

So if you think that I have forgotten someone or that my ranking doesn’t make actual sense, please share your opinion in the comments! I’d be thrilled to discover your own top fives.

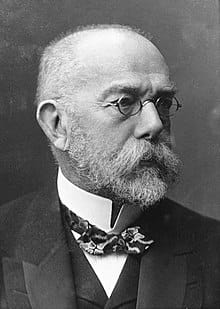

Robert Koch

To add some meat on that bone, here’s my personal list of people that could have made it to this top, starting with Robert Koch.

The famous German physician and microbiologist that discovered the causes and pathogens responsible for tuberculosis or cholera can be considered the founder of modern bacteriology and a main reason why we still aim to fight water-borne diseases nowadays.

Jackie King

Then, there are few rivers in the World, Jackie King hasn’t studied at some point in her rich career. The South-African researcher is one of the World’s most prominent aquatic ecologists. She demonstrated the intricate relationship between rivers, ecosystems, hydropower, agriculture, and humans.

Peter Wilderer

In a somehow similar fashion, Peter Wilderer has made a significant contribution to our understanding of the Water Cycle and sustainable water management, often using the river Danube as a case study.

Werner Stumm & James Morgan

Moving from Germany to Switzerland, I’d cite Werner Stumm, whose work together with James Morgan is the foundation stone of coagulation and flocculation in wastewater treatment.

Piet Odendaal

On a different level, Piet Odendaal strongly impacted the water sector’s landscape by merging the International Association on Water Quality with the International Water Services Association to create the International Water Association in the year 2000.

Osborne Reynolds

A bit more than a century before, Osborne Reynolds described the laminar and turbulent flows of Water within a pipe, gave his name to the Reynolds number, and far more significant, traumatized the young hydraulic engineer in me. Like, Really.

Gilbert Degrémont

Talking of my personal influences – I told you this top was subjective – I’d cite Gilbert Degrémont, that founded not only the company Degrémont, but also published the first Degrémont Water Handbook, that’s still sitting on my shelf today.

Diane d’Arras, Mark van Loosdrecht, Gerald Pollack & Matt Damon… and more!

In an Ideal World, I’d like to have the four next names on my podcast: Diane D’Arras, as a water industry expert, and the first woman to lead the International Water Association, Professor van Loosdrecht, to discuss his Annamox and Nereda breakthroughs and correcting me on the way to pronounce his name, Gerald Pollack, to address his discovery of the fourth phase of Water, and Matt Damon, because… well Matt Damon. No more seriously, as the co-founder of Water.org.

Even faster, here are the other names I considered when preparing that top: John Briscoe, Rita Colwell, Takashi Asano, Karl Imhoff, my Dad, Abel Wolman, and William Mulholland.

Again, please tell me in the comments who I am forgetting here because there are for sure dozens more that would deserve being in that top!

Most Influential People #1: The technology, that’s somehow in my garden

A century ago, the United Kingdom dominated the World, and it didn’t have only advantages. Indeed, being trapped in a rather small island, with high population density and soaring industry, the UK also faced rampant pollution.

As a consequence, they were one of the first countries in the World to focus on water treatment, notably with the establishment of the Royal Commission on River Pollution in 1874.

That had already led to the invention of BOD5 as a measuring unit for pollution levels and the famous 30:20 plus full nitrification effluent standard. But the largest contribution to the water industry’s timeline was still to come, with the invention of the activated sludge process in 1914.

The story of activated sludge actually starts two years before, when Gilbert Fowler, from the University of Manchester goes on a trip to the United States.

There, he visits the Lawrence Experimental Station, in Massachusetts, which was then an open-sky laboratory for wastewater treatment technologies.

At the time, they were working on the aeration of municipal wastewater, and it seemed to have quite good results, just so far for unknown reasons.

Introducing: Edward Ardern and William Lockett

Upon return to England, Fowler discussed what he observed abroad with Edward Ardern, a chemist at the Manchester wastewater treatment plant, and his co-worker William Lockett. He suggested both of them reproduce the American experiments.

That’s what they did throughout 1913 and the beginning of 1914. They used glass bottles filled with wastewater from various places of Manchester, and alternated aeration and decantation time.

But the big difference with the US tests is that Ardern and Locket didn’t empty the decanted sediment between batches. And that turned out to be very effective.

While a fresh reactor needed weeks of aeration to reach complete nitrification, a reactor stuffed with decanted sediments already some days old was able to trigger the same results in a matter of hours.

For sure, that sediment was really powerful, which made Ardern and Lockett think of activated carbon; hence they named their discovery activated sludge.

Establishing Activated Sludge

It’s funny to think that this name that stuck is intrinsically wrong: it would be discovered much later that it wasn’t the sludge that got activated but the biological micro-organisms inside that were using the pollutants as nutrients, and using oxygen to support their metabolic activity.

The uptake of activated sludge treatments was anyways very fast. It could have been even more spectacular if it hadn’t been for the patent litigation that saw Ardern and Lockett fight with Jones, Attwood, Frank, or Clark, with some major lawsuits, especially in the US.

Nevertheless, by the second half of the twentieth century, activated sludge had become the go-to and workhorse of wastewater treatment, with little if any change to the original recipe.

It even turned into a joke when professor Schaumburg published this graph in a paper called “65 years of efficiency progress in activated sludge.”

Actually, the graph shows that, despite intense research and publications, the efficiency of BOD removal hadn’t changed at all since the inception of the process.

But as I often tell my wife, get over it; you can’t change perfection!

The most influential people in the Water Industry: CONCLUSION

That’s it for my personal top five, I’d be thrilled to discover yours, so come tell me on social media 😀